Chapter 29 - The Agreement of Sale

Learning Objectives

At the completion of this chapter, students will be able to do the following:

1) Explain the purpose of a letter of intent.

2) Explain how the statute of frauds impacts real estate contracts.

3) Discuss the difference between commingling and conversion.

4) Describe at least two contingencies that may be found in a real estate sales contract.

5) Explain the difference between an addendum and an amendment.

29.1 Licensee's Role

Transcript

A real estate sales contract is the agreement between the buyer and seller of real estate that governs the transactions. In the most basic sense, the real estate sales contract contains the seller’s agreement to sell and the buyer’s agreement to buy the real estate at a specific price.

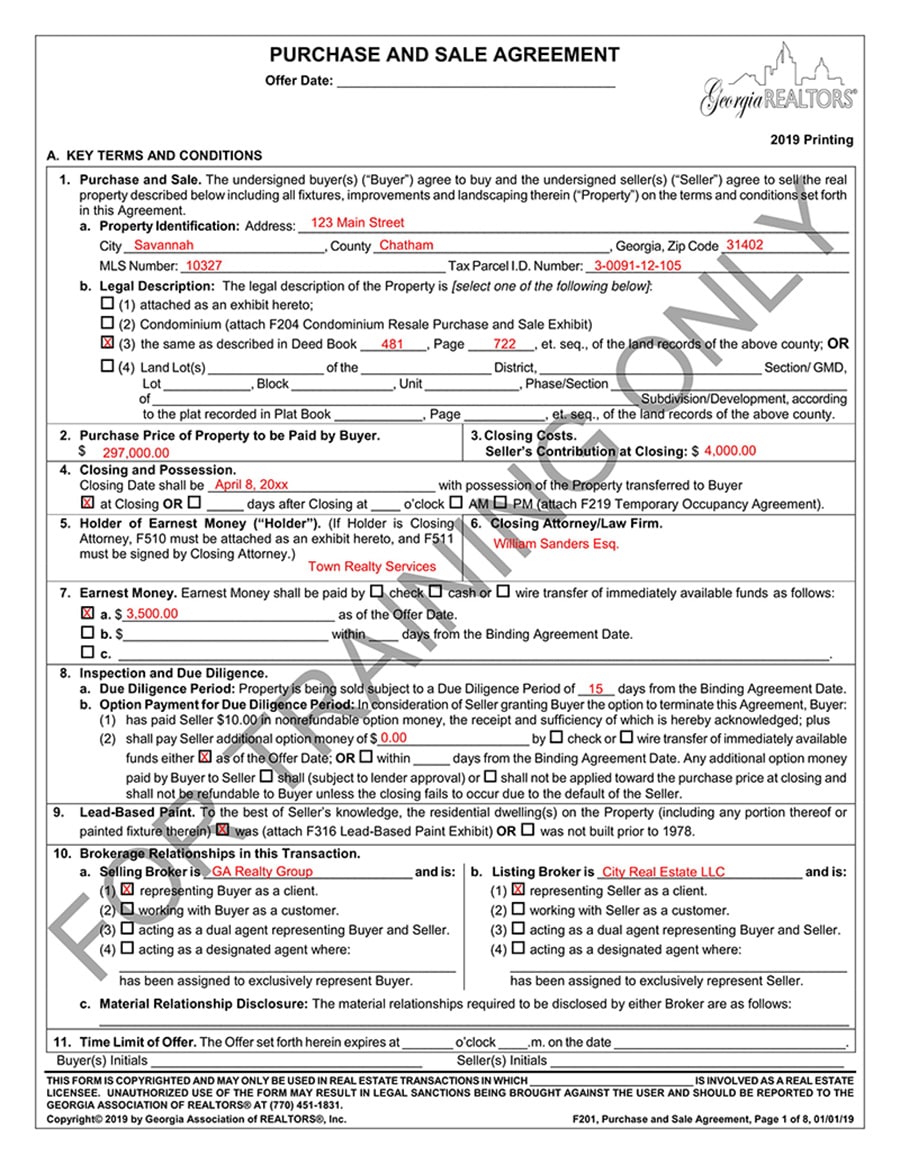

The real estate contract contains various warranties, or promises regarding the ownership, condition, and title status of the real estate. Contingencies for things going wrong, like destruction of the property, or the buyer’s inability to obtain a loan, are also included. Depending on the state, a real estate sales contract can be four to fourteen pages. For commercial real estate, a purchase and sales contract could be one hundred pages long!

The real estate contract, also called an agreement of sale, represents a meeting of the minds of the parties. Both the buyer and seller have certain terms and conditions that want as part of the transaction. By having everything written down in the real estate contract, an objective party (like a closing attorney or a court of law) can determine what the parties want and intend. If there is a question of whether the light fixtures were meant to be included in the sale, one only has to look at the written contract.

A meeting of the minds is necessary to have a valid contract. Often there are questions of whether the parties even have an enforceable contract. If the buyer sends a contract draft to the seller, and the seller sends a different draft to the buyer, have they made a meeting of the minds?

The answer depends on a number of factors. Did the buyer go forward with the transaction after receiving the seller’s draft? Was money exchanged at some point? Was there a repudiation or rejection? Without a meeting of the minds, the courts will not enforce a contract. Specific performance of the terms of the contract or monetary damages will not be ordered if there was, in fact, no contract.

The real estate sales contract can be prepared by a number of different people. Who prepares the contract usually depends on the state where the real estate is located, the type of real estate, and the local laws and customs of the jurisdiction. In theory, a buyer or seller could prepare their own real estate contract. There are countless cases on the books where an individual, looking to save money, drafted their own real estate contract. There was a famous case in Georgia where a contract for a $700,000 parcel of commercial real estate was drafted on the back of a napkin on the hood of a car. Real estate professionals, lawyers and non-lawyers alike, strongly discourage this practice because of the inevitability of conflict.

In states like New York, real estate contracts are generally drafted by licensed attorneys. Real estate brokers and agents show the property and negotiate basic terms, but the contract itself is worked out by lawyers. In other states, the real estate contract is drafted by non-attorney real estate agents. The agents are licensed by the state, are required to pass exams, and maintain professional standards through continuing education. Real estate agents work under the supervision of licensed, real estate brokers. Real estate contracts prepared by agents are usually “fill in the blank” forms that are universally used by all agents in the state. The forms are provided by local real estate agent associations, and have been prepared and vetted by local attorneys.

Pennsylvania has another category of real estate professionals called licensees. A licensee is authorized to prepare a real estate contract, but do little else. They are no agents or brokers. And they are certainly not attorneys. A licensee is essentially a scribe who put the terms of a real estate contract into a prepared format. The licensee cannot negotiate on behalf of, or represent, either party in the real estate transaction.

These variables usually only apply to residential real estate contracts. For commercial real estate contracts, except for limited, small transactions, these contracts are almost universally drafted by attorneys. Commercial real estate contracts are very complicated, and involve different types of real estate with buildings that can have a number of uses. The use of the building, the condition of the land, financing terms, environmental considerations, and transfers of leases are all part of a typical commercial real estate transaction.

Because the role of licensees is limited by law, one must be very careful not to drift into the unauthorized practice of law. Unauthorized practice of law occurs when a non-lawyer (a person without a valid law license) provides legal advice to another for a fee or other consideration. The most obvious case of unauthorized practice of law is when a non-lawyer represents another person in court, through personal appearance in the court or written pleadings. That’s easy. In the context of contract negotiation, the line is rather blurred.

Is advising a prospective buyer about a fair purchase price legal advice? Likely not. The price of the real estate is purely a business matter. But what about negotiating contingencies if the sale falls apart? The agent is then required to tell the party about the implications and definition of default, and how to best handle that situation. That is far closer to legal advice. Agents are, of course, licensed and permitted to give limited advice in their narrow field. Licensees on the other hand are more like scribes. They write the terms the others tell them, and leave the rest to the attorneys.

The unauthorized practice of law is a crime in many states. If a licensee is convicted of unauthorized practice of law, he may have his license suspended or revoked, and he may be fined for violating state law. These are very serious implications, especially if one relies on that license for the livelihood. Any time the licensee wishes to apply for another license in another industry, they’ll be required to disclose the suspension or revocation of their licensee privileges.

When there’s even the slights question of whether certain advice falls into the practice of law context, it is best to let the attorneys handle it. Attorneys should be the ones to negotiate and modify a real estate contract, in states where that is the norm. With attorneys, there is never a question about unauthorized practice of law.

Key Terms

Agreement of Sale

A written agreement or contract between seller and purchaser in which they reach a “meeting of mind” on the terms and conditions of the sale. The parties concur; are in harmonious opinion.

29.2 Negotiating the Agreement

Transcript

The real estate purchase and sale agreement, sometimes called the real estate contract, is a written document binding the owner of real estate to sell that property to the buyer, and similarly obligating the buyer to purchase the real estate from the seller. The real estate contract identifies the parties to the agreement, specifically the buyer and seller, sets out the proposed date for the closing, provides disclosures and warranties of the seller, and gives instruction in the event the contract is breached or cannot be performed. A standard residential real estate contract can be as short as a few pages, while a complex commercial real estate contract can be as long as one hundred pages. Because these agreements are so complex, and the details open to discussion, the process of negotiating the real estate contract can be daunting.

While a buyer and seller are free in the US to negotiate their own real estate contract, it is more common for an agent representing each party to negotiate on behalf of their client. Real estate agents are trained and licensed to represent buyers and sellers. They’re also more experienced in understanding the intricacies of the standard real estate contract, and familiar with the local market standards and practices for real estate closings. The agent is therefore responsible to their client, the principal. The agent is obligated to advise the client of negotiating positions, offers from the other side, and what is best and reasonable to secure the principal’s interest in the real estate contract.

The agent has a fiduciary duty to present all offers to the principal, their client. This includes basic offers like the purchase price of the real estate, and small details like the furniture being left behind. The duty to present all offers includes unreasonable offers. If the seller wishes to list his real estate for sale at $300,000, but a prospective buyer submits a written offer of $100,000, the seller’s agent is obligated to let the seller know about the offer and give him a chance to reject it. Why? There may be circumstances about which the agent is unaware that would cause the seller to accept even a low offer.

In order for the real estate contract to be binding there must be offer and acceptance. Acceptance establishes a meeting of the minds. A contract cannot be binding if both sides do not agree to all the terms in the contract, so that their minds have met as to everyone’s obligations in the agreement. Often, we refer to the offeror and offeree. The offeror is the party making the offer, and the offeree is the party receiving the offer. Because these words sound alike and have little practical application, let’s refer to the buyer and seller. Almost always, the offeror is the buyer.

The seller has listed the real estate for sale on the market, and the buyer wishes to make an offer to purchase the real estate at or below the listed sale price. In a basic format, the proposed buyer would present an offer in the form of a complete real estate contract, or in an offer sheet, to the seller. The seller would then sign the offer sheet or contract establishing a meeting of the minds.

But what if the seller disagrees with certain terms of the offer. Then the seller could reject the offer by presenting a written rejection, or allowing the time for acceptance to elapse. But if the seller thinks that he can get the buyer to agree to his terms, the seller can make a written counteroffer. The counteroffer is an offer in itself. A counteroffer is also a rejection of the first offer. A counteroffer does not create a contract with the buyer until the buyer accepts the counteroffer. Again, offer and acceptance and required to form a contract. Whether it is an offer or counteroffer, there must be acceptance, and a meeting of the minds as to which offer is being accepted by both parties.

In turn, the buyer receives and considers the counteroffer from the seller as an offer unto itself. The buyer can accept the counteroffer, reject the counteroffer, allow the counteroffer to expire, or make a counter-counteroffer of his own. The cycle may continue numerous times until all of the terms are agreed to by both sides. The terms of the agreement must be exactly the same when both sides accept; otherwise, there is no contract.

There are numerous ways to make an offer. In many residential real estate transactions, an offer is made by sending a complete real estate contract to the seller. The offer will have an expiration date. Either the seller signs his agreement to the contract, makes a written counteroffer, rejects the offer, or allows the offer to expire. In other residential real estate transactions, and in most commercial real estate transactions, the offer is made by a Letter of Intent, or LOI. The letter of intent is, essentially, an agreement to make a contract.

A letter of intent is usually drafted by the buyer's agent or attorney. It's offered after the basic terms of an agreement are negotiated by the buyer's and seller's agents over the phone, by email, or in a meeting. The letter of intent contains the basic terms of the agreement that will be put into a complete real estate contract. The terms include the names of the buyer and seller, the address and basic description of the real estate being sold, the purchase price, the proposed date of the closing, the name of the closing attorney or title company, the expected terms of the mortgage loan buyer will take to purchase the property, basic warranties by the seller about the property and his ability to sell, and conditions precedent to the closing.

Conditions precedent usually involves the condition of the real estate. The buyer may require the seller to pay off certain liens or clear certain title issues before the contract is signed. The buyer may require the seller to clean up an environmental problem or another defect on the property. Often times, the seller will require the buyer to produce proof of sufficient funds or a loan commitment from an established lender to prove that the buyer can complete the transaction. Often, conditions precedent involves an inspection. The buyer will want to do a pre-inspection of the property to make sure it is suitable for their needs. Thereafter, the contract drafting may proceed.

Generally, the letter of intent is not a binding contract in itself. Courts often say that an agreement to agree is not an agreement. This is because there is usually no consideration. During the letter of intent period, neither side has given up anything of value to obtain the other party’s agreement to the letter of intent. Money does not usually change hands at this stage, nor is money placed in escrow. Further, the seller usually keeps the property listed on the market during the letter of intent period, so the seller has not given up any potential sales.

The letter of intent will also list the time period allowed to draft the real estate contract. If the real estate contract has not been signed by the deadline, the entire agreement may be voided, unless the parties agree to extend the time period.

One example of how letter of intent and the real estate contract work together is from a recent transaction in suburban Atlanta. A community center was purchasing a commercial building that had been used for industrial purposes. The building required extensive renovation to convert it to the new use. Both parties understood this and much of the agreement allowed for the property to be purchased as is. However, the buyer was concerned about the HVAC, or air conditioning and heating units, on the roof of the building. They were not adequate to cool the building, were old, and worn out. In fact, one of the units was leaking fluid into the building. Someone had to pay for new HVAC units. However, before writing the letter of intent, both parties agreed on a price. The buyer could not go up on the price because the mortgage lender would not approve of a higher loan. The seller could not go down on the price because he had to pay off an existing mortgage. The parties agreed that the seller would replace the HVAC units with specific instructions on the type off units to install, and he would take a tax deduction for the business expense, thereby allowing the contract to go forward. A letter of intent was drafted and signed with the provision that the seller replace the HVAC units as instructed.

A real estate contract was drafted and signed by the parties, which included the provision that the seller had replaced the HVAC units with four new 20,000 BTU machines. Soon after the closing, the buyer encountered a problem during the renovation of the building. Specifically, there was not enough electricity for the building to operate. The problem was traced back to the HVAC units that were sapping too much electricity. The new owner went up on the roof and found that the seller had not installed four 20,000 BTU units, but rather eight 10,000 BTU units. The building could not handle the electrical load, and this was a violation of the letter of intent and the contract.

The parties went to court. The seller argued that the letter of intent was not a binding contract and the buyer accepted the building as-is in the real estate contract. The buyer argued that replacement of the HVAC units as instructed was a material condition of the contract, and the letter of intent was binding because it was written in the contract.

The court never got to rule on the issue. Like more than 90% of cases, this settled. The HVAC contractor admitted that he made a mistake in the installation and replaced the units, and installed the correct units on the roof.

When the real estate contract is prepared it must be in writing. There is an ancient law called the Statute of Frauds that requires agreements for the transfer of real property to be in writing. In law school, many law students call this the statue of frogs. With that phrase, you’ll never forget its meaning or importance. If an agreement to buy, sell, exchange, or encumber real estate is not in writing, then the contract may be void, and it cannot be enforced in court. The reason for this is, exactly as the statute says, fraud. Real estate is very important and inherently valuable. The courts have reasoned over the centuries that no one would enter into an agreement to buy or sell real estate without writing it down. Therefore, if someone comes to the court with an agreement to purchase real estate that is not in writing, the courts will look upon this agreement with suspicion and usually rule it invalid. The potential buyer or seller could not get a court to order the transaction to go forward on an unwritten real estate contract. Nor could either side claim monetary damages with an unwritten real estate contract.

The Letter of Intent, once signed, leads to the drafting and eventual execution (or signing) of the real estate contract. The terms contained in the Letter of Intent are filled into the real estate contract, and the rest of the contract is drafted around them. There may be differences between the letter of intent and the real estate contract. However, it is likely that one of the parties will object and demand that the terms of the letter of intent govern and be placed into the contract. The real estate contract can be drafted by either the buyer’s or seller’s attorney. Local custom governs who does the drafting. Once the real estate contract is signed, that is a binding agreement that can be enforced in court.

The real estate contract must be signed by both parties. Often, the real estate agents themselves also sign the real estate contract. Both parties must sign the real estate contract to show that both parties agree to the terms. Without a signature from one party, it must be assumed that the non-signing party did not agree to the terms.

Key Terms

Counter Offer

A response to an offer to enter into a contract, changing some of the terms of the terms of the original offer. A counter offer is a rejection of the offer (not a form of acceptance), and does not create a binding contract unless accepted by the original offeror.

Letter of Intent (LOI)

Generally an agreement to agree. It outlines the terms between parties who have not formalized an agreement into a contract. LOIs are generally not binding and unenforceable.

Offer and Acceptance

Elements required for the formation of a legally binding contract. The expression of an offer to contract on certain terms by one person (the “offeror”) to another person (the “offeree”), and an indication by the offeree of its acceptance of those terms.

29.3 Necessity For Written Agreements

Transcript

Can a person or company sell their real estate based on a handshake? What about a nod and a wink? In theory, a person could sell their land with just a handshake by taking money or something of value, and writing the new owner a deed for the property.

But what if one of the parties to the handshake backs out? What happens to the handshake deal if the seller wants more money than the buyer originally offered? What happens to the nod and wink deal when the seller wants to swap out the land for another parcel? Are any of these agreements enforceable in court?

The short answer is no.

In order for a real estate purchase and sale contract to be valid it must be in writing. An ancient principle of law called the Statute of Frauds requires that certain contracts be in writing to be enforceable. Many law students refer to this as the “statue of frogs”. It’s hard to forget that. The theory behind the Statute of Frauds is that certain contracts are so important that no rational person would entrust the terms to an oral agreement, therefore to be valid, they must be written down.

The statute of frauds is a function of state law. Many states have written the statute of frauds into their commercial or contracts codes. Each state has its own peculiarities, but the basic concepts that we discuss below are universal in common law states. The statute of frauds is also interpreted by precedents from state court decisions. For applications and interpretations of the statute of frauds in your jurisdiction, it is best to speak with a licensed attorney.

The statute of frauds applies to all types of contracts and agreements regarding real property. The most well known is the purchase and sale agreement, also called the real estate contract. Any time an interest in real property is being conveyed it requires a written document; for example a security interest. This is commonly called a mortgage. When a real estate owner gives a mortgage to the bank in exchange for a loan, a security interest in the real property is conveyed. This requires a written document. An oral mortgage contract will be unenforceable. That doesn’t mean the borrower won’t be personally liable for the debt. While the borrower can be sued in court for the money borrowed, there will not be a lien on the property because of the loan itself. The lender will not be able to foreclose on the property based on his security interest alone.

Leases must also be written out as documents. A tenant who leases a property without a written lease document is considered a tenant at sufferance. The landlord can evict the tenant at any time. But the landlord will not be able to make a claim for rent, because there wouldn’t be evidence of an agreed-upon sum for the rent.

Other real estate-related documents that require writing include an option contract, an easement, and a conveyance of specific rights, like the right to harvest produce or underground mineral rights. That statute of frauds doesn’t just include contracts related to real estate. A contract that cannot be performed within one year is also governed by the statute of frauds. A simple example is where a person hires a painter to paint his house, but not to paint it immediately, to paint it 18 months from the date the contract is signed. Unusual as it may sound, these types of contracts are common in certain industries. And they must be in writing.

A contract for the sale of goods for $500 or more must also be in writing. For example, if a person orders a television that costs $1,000 from a store to be delivered, if the contract for the sale is not in writing, it’s not enforceable. Most businesses function this way, by ordering parts or inventory to be delivered, rather than going to a warehouse or store to immediately pick it up. In daily life, we rarely think about this. When you order something online, there is a written contract for the purpose. The buyer is obligated to pay for the goods and the seller is obligated to ship them to the buyer. If the buyer doesn’t pay, then he will not get the goods. If the seller doesn’t ship the goods, the money must be sent back. If there is a written agreement, either side can go to court to compel the sale.

If the goods delivered aren’t exactly what the buyer ordered in the contract, then the seller can be forced to take back the goods and send the correct items or may have to pay damages. A simple example is where a person orders a 50 inch television from Best Buy, signing a contract and all, but Best Buy delivers a 20 inch television. Best Buy is obligated under the written contract to provide the correct item. If it can’t, it must return the buyer’s money. If the buyer, for whatever reason, suffered damages, he can make a claim for breach of contract. However, if there is no written agreement, and there is no way for the court to know exactly what items were ordered, the buyer will have no recourse and may be forced to keep the smaller television.

Another category of contracts that are required to be in writing is collateral contracts. Collateral contracts are agreements to enter into a contract, but money is exchanged for the right to enter into the contract. In another section we talked about the letter of intent to enter into a real estate contract. The letter of intent, by itself, is not a contract. It’s just a list of terms that both parties want to see in a final contract. It is generally not enforceable in court. However, if you add consideration into the mix, or money to induce one party to sign, then we have a collateral contract. The letter of intent would be enforceable, because something of value was given in exchange for the right to enter into the final contract.

But what if there is no writing. If the buyer gives the seller $10,000 to enter into a real estate contract, but without a signed letter of intent, then the agreement to enter into the agreement is not enforceable. The seller would certainly have to give the money back if the deal is not consummated, but a court cannot compel the parties to enter into a final real estate contract. As the maxim goes, a contract to enter into a contract is not a contract. Not unless it is written down and something of value was exchanged for the right to enter into the final contract.

Once you have your written contract, can a court consider your notes, emails, letters, or other writings to interpret the contract? Generally, no. This is called the “parol evidence rule”. The parol evidence rule is another ancient common law concept that is a bedrock of American contract law. The parol evidence rule prevents a party from using extrinsic evidence to create an ambiguity in a contract, or to add to a contract that is whole in its terms. Let’s break this down and put it back into English.

The first part - extrinsic evidence

This is any writing or document, or evidence in general, besides the original contract. Courts will not allow a party to present anything from outside the contract that would make the contract seem ambiguous, and try to resolve the ambiguity. The courts want parties to put all of their terms into a single contract and rely only on that document. For example, in a real estate contract, if there is a sentence that says all fixtures in the home are being sold with the home, a party cannot introduce a letter that is not part of the contract that lists the fixtures. It points out an ambiguity in the contract and resolves the ambiguity. In the case of an ambiguity, courts want to rely on the law rather than outside documents. The preferred method would be for the parties to specifically make the letter or the list part of the contract at the time it is signed.

The second part (about adding to a contract) talks about a contract that has all of its terms written in, thereby making it whole. In this case, if a party to a complete real estate contract introduces a letter that says, “we agree that a car is being sold with the land,” this will not be considered by the courts to be part of the real estate contract. It is an addition to a contract that is already whole.

There may be a separate agreement to buy or sell a car, but it cannot be enforced as part of the real estate contract.

In some states, the parol evidence rule is called the “four corners doctrine” because it requires the court to look only at the four corners of the signed contract in determining the responsibilities of each party. Some states are more lax than other when it comes to enforcement of the parol evidence rule.

Key Terms

Statute of Frauds

A state law, based on an old English statute, requiring certain contracts to be in writing and signed before they will be enforced at law, e.g., contract for the sale of real property.

29.4 Statute of Frauds in Georgia

Transcript

The Georgia statute of frauds is spelled out under Title 13, Chapter 5, Article 2 of the Georgia Code.

It specifically states the following:

To make the following obligations binding on the promisor, the promise must be in writing and signed by the party to be charged therewith or some person lawfully authorized by him:

(1) A promise by an executor, administrator, guardian, or trustee to answer damages out of his own estate;

(2) A promise to answer for the debt, default, or miscarriage of another;

(3) Any agreement made upon consideration of marriage, except marriage articles as provided in Article 3 of Chapter 3 of Title 19;

(4) Any contract for sale of lands, or any interest in, or concerning lands;

(5) Any agreement that is not to be performed within one year from the making thereof;

(6) Any promise to revive a debt barred by a statute of limitation; and

(7) Any commitment to lend money.

Key Terms

29.5 Earnest Money Deposits

Transcript

When a buyer makes an offer to purchase real estate and the seller accepts, the parties enter a period of preparation and due diligence. The time between signing the real estate contract and the closing could be a matter of days or months. During that time, the buyer is securing financing, inspecting the property, and performing a search of the title and tax records. And during this in-between time, the seller usually takes the property off the market and stops considering additional offers of purchase. What is to stop the buyer from walking away from the deal if, for whatever reason, he is no longer interested in purchasing the real estate?

The answer is earnest money. Between the real estate contract signing and closing, the seller has given up something of value. He has given up the opportunity to potentially accept a better offer. If the buyer backs out of the deal, there is a chance the seller could lose money and/or time. The seller has an incentive to see the contract through to the closing. But without earnest money, the buyer does not have the same luxury.

Earnest money is cash held by a third party to guaranty that the buyer completes the transaction. A typical earnest money transaction goes like this... the buyer makes a written offer to the seller to buy real estate. At the time the parties sign the contract, the buyer deposits five thousand dollars with an escrow agent. This is earnest money. The escrow agent has a signed contract with the parties. Typically, the contract says that if the closing takes place, then the earnest money is given to the seller, and the buyer is credited with having already paid five thousand dollars. However, if the closing is not completed, then what happens to the earnest money has to be resolved.

The purpose of earnest money to make sure the buyer completes the transaction and does not back out for good cause. It is a financial penalty. The amount of the earnest money is supposed to be proportional to the risk the seller takes when the real estate is taken off the market. It is usually a percentage of the purchase price. It should be high enough that the buyer would not want to lose the money by backing out of the transaction arbitrarily. But not so high that it far exceeds the damage the seller could claim for losing better offers.

The amount of earnest money is always negotiable. The buyer's agent will want to minimize the sum, so that a large amount of the buyer's cash isn't held up during the due diligence period, and the hit to the buyer's finances will not be so severe if the transaction falls apart. The seller's agent will want to maximize the amount of earnest money to keep the buyer honest and provide the greatest incentive (or threat) for the buyer to get to closing. Both the buyer's and seller's agents will have to understand that if their demands are too extreme, the real estate contract will not be signed and both parties will lose out on the opportunity for a purchase and sale. Not to mention the lost commissions for the agents.

Technically, earnest money is not required in any real estate transaction. However, it has become standard practice in most jurisdictions because it filters out those buyers who are not serious about closing and purchasing the real estate. Also, the earnest money system avoids litigation and saves parties thousands in legal fees.

Earnest money can be held by any responsible person or company. Who holds the earnest money is a matter of local custom and local law. In some states where a title insurance company acts as the closing agent, the title company holds the earnest money. Some states have the seller's agent hold the earnest money. In states where a closing attorney sits between the buyer and sell acting as a neutral, the closing attorney holds the earnest money. And in many places, it is common to have a professional escrow company or a bank hold the earnest money.

Earnest money must be held in an escrow account. Escrow means that the funds are not commingled or mixed with the personal money of the escrow agent. Escrow money is sacrosanct. That money is held in trust, for the benefit of third parties. It is the property of the buyer or seller. If a real estate broker serves as the escrow agent in the transaction, and is found guilty of commingling the escrow funds, the broker could lose their license, or at least have it suspended. For attorneys, commingling escrow funds with other money is a severe ethical violation that results in suspension from the practice of law, or loss of a bar license. It's that important. If an escrow agent keeps the money, that is a crime and a civil tort called conversion. Conversion is the misappropriation of another's property. Trust funds or escrow funds are property of another. If an escrow agent converts escrow funds, he will find himself in court facing civil damages and possibly jail time. Again, it is that important.

Aside from holding the money and disbursing it to the seller when the closing is completed, what does the escrow agent do? The escrow agent decides what to do with the escrow money if there is a dispute. Sometimes, the buyer backs out of the transaction for good cause, such as inability to get lender financing, or a major defect in the property. In that case, if the escrow agreement and real estate contract say so, the escrow money should be returned to the buyer. The real estate contract and escrow agreement list the reasons the escrow money should be returned to the buyer. If the buyer backs out without good cause, as written in the real estate contract, then the escrow agent gives the money to the seller.

What happens if the case isn't so clear? For example, if the buyer backs out of the transaction claiming there is a major defect with the real estate, but the seller believes the defect doesn't exist and the buyer is backing out for no reason, should the escrow agent act as a judge? No. In that case, the escrow agent files a lawsuit in the county court known as an interpleader. The escrow agent names the parties to the transaction as the parties to the case, deposits the escrow money with the court, and sets away to allow the court to decide who gets the escrow money.

Key Terms

Commingling

The illegal mixing of personal funds with money held in trust on behalf of a client.

Conversion

The unlawful appropriation of another’s property, as in the conversion of trust funds.

29.6 Components of the Agreement

Transcript

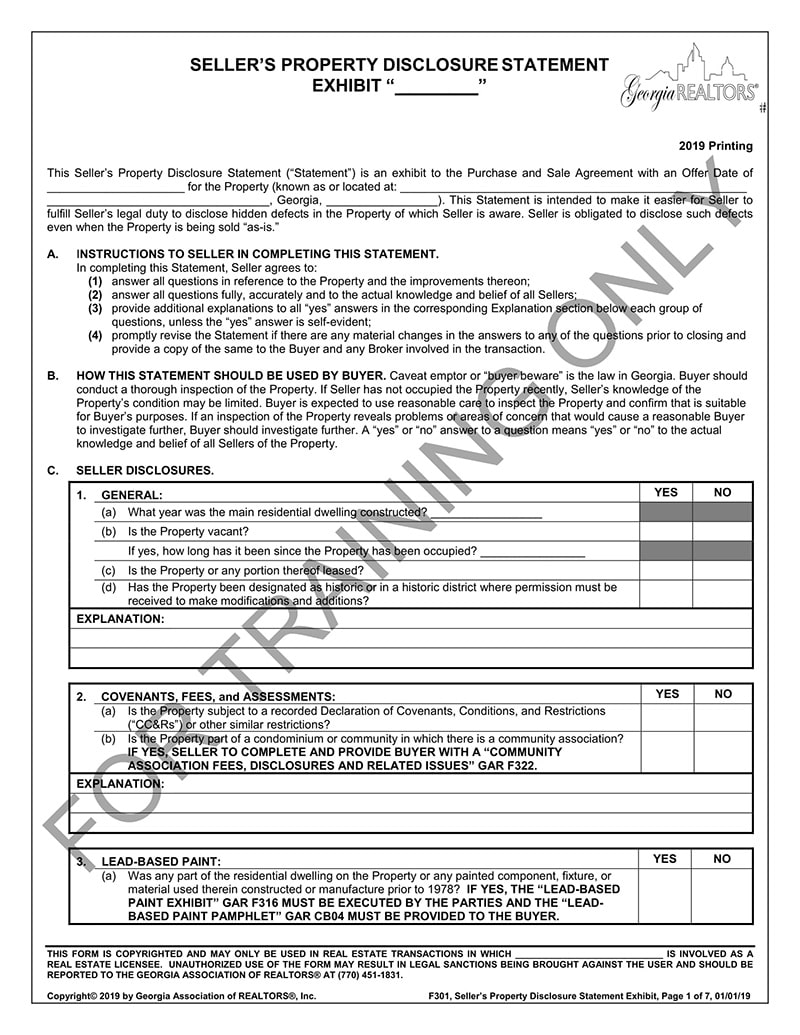

The real estate purchase and sale agreement, also called the real estate contract, is the backbone of every real estate transaction. The terms of the real estate contract are numerous and often complicated. Understanding each section of the real estate contract, the standards for negotiation, and the rights and responsibilities of each party is an essential skill for every real estate professional.

In order to have a contract for real estate, all we need are parties who are legally competent, a written document identifying the real estate to be sold, for how much money, when, and the parties' signatures. Indeed, a real estate deal could be written on a cocktail napkin. But what happens when something goes wrong? What happens when the parties are unsure about a material detail of the agreement? Will there be a deposit? Who holds it? What happens if a party backs out? What happens if the buyer backs out because he can't get a loan? Does the seller really own the property? What about liens, easements, and claims others may have to the real estate? Will the seller protect the buyer if there is a question about his ownership down the line?

That's why in the United States it is common to use a longer, more complicate real estate contract. Every section of the real estate contract is there because there have been numerous lawsuits about that specific term. And the term was added to standard real estate contracts to avoid lawsuits down the road.

Let's first break down the sections of a standard real estate contract.

The introduction will have the names of the parties. The buyer and seller are identified. In standard residential real estate contracts, this will just be their names. There can be more than one buyer or seller. For the seller, all owners of record must be listed. Usually for married couples, both spouses will be listed. If one of the parties is a corporation, partnership, or other entity, the entity will be listed, along with their state of incorporation or organization. If an entity is a party, a human being has to sign on behalf of the entity, in their capacity as a duly authorized representative. This will be at the end in the signature block.

At the beginning, you will often see the date of the contract. This is very important. Many of the terms of the contract relate back to the date the contract was signed. As we'll discuss later on, the buyer may have thirty days to inspect the property from the date of the contract. Or the closing must take place within sixty days of the date of the contract. Often with residential real estate contracts, a proposed contract is the offer made by the buyer to the seller, and the offer is valid from a certain number of days from the date of the contract. The contract date is also important in determining priority of offers. If multiple offers come in, or multiple contracts are signed at the same time, the contract signed first is usually valid, while the later contracts may be invalid because the parties have already entered into a commitment.

Next in the real estate contract is identification of the property. At this point in the contract, the property is usually described by its address. The address should include the country, city, and state. Attached to the real estate contract as an exhibit is the legal description of the property. The legal description is the technical description of the boundaries and location of the real estate.

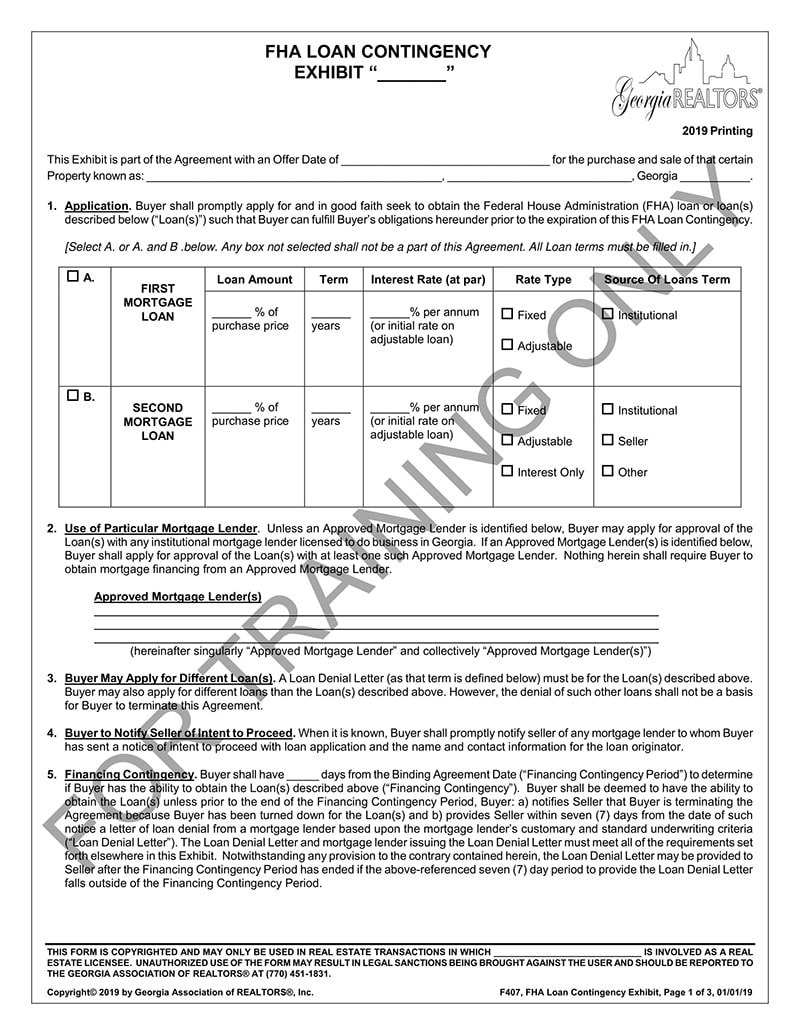

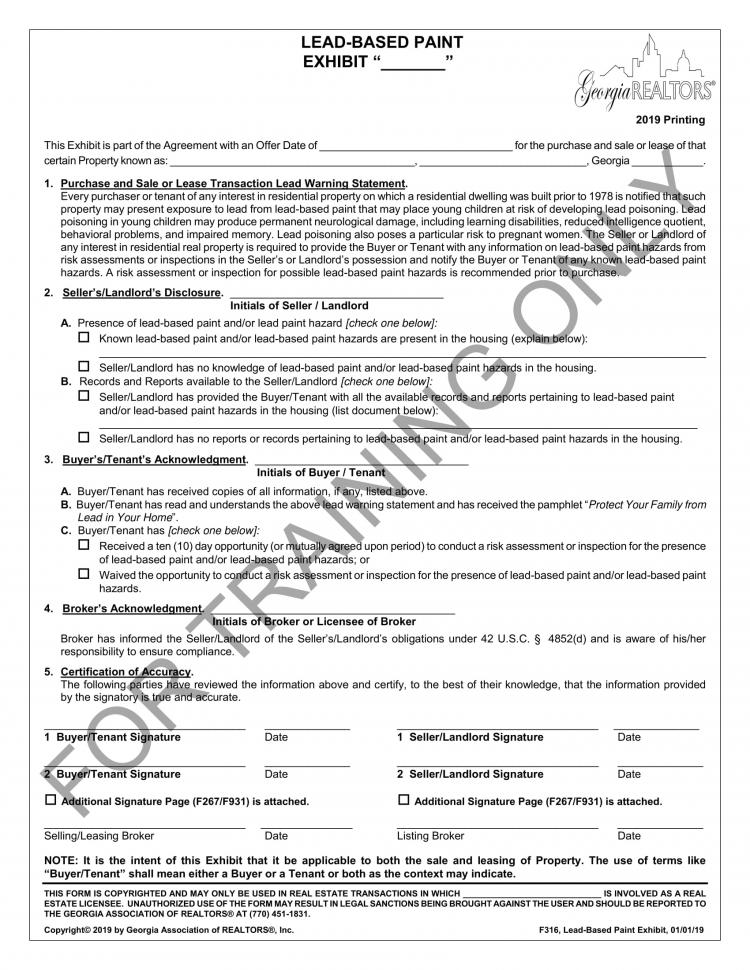

The purchase price usually appears next in the real estate contract. The purchase price clause includes the method of payment. Will the buyer pay with cash, a mortgage loan, or a combination? The clause will describe what percentage of the purchase price will be a down payment and what percentage will be financed through a lender. Often, this clause contains a contingency, that the contract will be voided if the buyer is unable to get a mortgage at certain terms. The terms usually include a ceiling interest rate and maximum down payment. The purpose of this clause is to make the contract feasible. The buyer knows, or should know, how much he can afford to pay each month. If a bank will not offer terms to make the payment feasible, then the buyer should not be forced to follow through with the contract.

Along with the purchase price, the real estate contract will state whether any earnest money has been paid by the buyer, and who is serving as the escrow agent for the earnest money. The earnest money serves as a commitment by the buyer to complete the closing and to not back out of the contract with good cause. Along with a description of the earnest money, there are stated terms and conditions of what happens to the earnest money when the closing succeeds or if the contract is voided.

The real estate contract will list the closing date. The date is usually an end point, meaning that the closing will not take place after a certain date. The date is usually flexible, and the contract will allow the parties to mutually agree to change the closing date. With the closing date, the contract usually lists the closing attorney or closing agent. Local custom dictates who selects the closing attorney. It may be the mortgage lender, the buyer, or whichever party is paying closing costs.

The next section of the contract gets more legalistic. There is a recitation of the seller's ownership interest, and how the owner will provide evidence of ownership. This section will describe how and what title are legally conveyed to the buyer when the closing takes place. This is where the warranties are made. We'll discuss warranties in a bit.

Next comes the issue of proration. When the buyer takes title to the property, he will immediately become responsible for real estate taxes, utilities, homeowner association dues, and all expenses of the property. Odds are the closing will take place in the middle of the month. The seller may have paid some of these expenses in advance, and is entitled to the prorated, or a portion, of the expenses to be reimbursed. In other words, if the seller paid $100 for the trash pickup in advance for the full month, and the closing takes place on the 15th of the month, then the buyer has to pay the seller back $50 for the portion of the month that the buyer owns the property. In many states and counties, real estate taxes are paid annually, so the calculation has to be done to calculate how many days of the year have been paid for, and how many days have to be reimbursed.

The opposite is true as well, if bills are paid at the end of the month, like the electric bill, then the seller will have to reimburse the buyer after closing. In this scenario, money is usually held by the closing attorney in escrow, based on estimated bills from past months. Sometimes the service provider or utility will give you a total due as of the date of the closing and estimation won't be necessary.

Proration is done by dividing the bill by the number of days in the month or year, depending on how often the bill is paid, and counting the days before the closing as the seller's responsibility, and the days after the closing as the buyer's responsibility.

The contract then moves on to talk about default. Default is when one of the parties fails to fulfill the terms of the contract. In the context of a real estate contract, default usually means failing to close. The default section describes the different types of default, the reasons for default, and the remedies available to each party in the event that the other defaults.

Common situation of default include the buyer simply refusing to buy, the seller refusing to sell, the buyer being unable to get financing, or some other glitch in the due diligence process. Each has its own remedy.

When the buyer simply refuses to close without good cause, then the usual remedy is for the earnest money to be turned over to the seller as a penalty. The seller usually does not have the right to sue the buyer to force closing. Courts are generally unwilling to force a closing on an unwilling buyer. He may refuse to buy because he doesn't have the money. Turning over the earnest money is called liquidated damages. It is the amount of money that the seller estimates he lost by entering into the contract, and the damages sustained by the buyer's default. In order to collect liquidated damages, the earnest money clause and the default clause have to be written with specific language, with each state having its own law as to the required language.

When the seller defaults and refuses to sell, the buyer will get the earnest money back. But depending on the terms of the contract, the buyer may be able to sue the seller to force a closing. The buyer may also be able to sue for lost profits or other benefit that the building would have provided him or other damages if the buyer has to buy a more expensive property. Since the opportunities for lawsuit are numerous, contracts often limit the buyer's remedy to collecting the earnest money.

If the buyer defaults because he could not obtain the financing required by the contract, then usually the earnest money goes back to the buyer. If the buyer refuses to close because during the inspection of the property or inspection of the title something turned up that would make closing impossible, or things are contrary to the warranties made by the seller, then the earnest money goes back to the buyer.

Another event of default is usually insolvency, or bankruptcy. If one of the parties goes into bankruptcy then the contract is usually voided. Bankruptcy law will not allow a buyer in bankruptcy to complete the transaction. If the seller is in bankruptcy, the real estate becomes the property of the bankruptcy trustee. The trustee may allow the closing to go forward, but isn't under any obligation to do so.

Along with the events of default are the contingency clauses. A contingency clause states a requirement for the closing to happen, or an event that could cancel the closing. A contingency clause says: "the closing will take place if this happens" or "the closing will not take place if this happens." The most common contingency clause is referred to as the mortgage contingency. As we said earlier, the mortgage contingency goes back to the purchase price. If the buyer is financing a part of the purchase price, he has an opportunity to obtain a mortgage loan under terms that are feasible, meaning an interest rate, term, and down payment of certain amounts. If the buyer, after diligent effort, is unable to obtain a loan that falls within the contingency, the contract can be canceled without penalty.

Another common contingency is inspection. The buyer is given an amount of time to go on to the property and physically inspect it. Often the buyer brings in an engineer or contractor to make sure the building is structurally sound, and to identify any defects that the untrained eye might miss. If the property does not satisfy the inspector's standards of a structure that does not require extensive renovation, then the contract may be canceled.

A home sale contingency is for the buyer's benefit. It allows the buyer time to sell his old home first so that he can afford to buy the new home. Often, the buyer is able to schedule the two closings consecutively, first selling his old home, then using the sale proceeds to buy the new home. However, if the buyer is unable to sell his old home within a given time, this contingency clause allows the buyer to cancel the contract.

Another contingency is the insurance contingency. In this clause, the buyer is given an opportunity to obtain property insurance covering the real estate. This is rarely a problem. But if for some reason the buyer is unable to obtain insurance, the contract can be canceled.

The insurance contingency has another extension, namely title insurance. As part of the closing and inspection, the buyer will review the title history of the subject real estate. If the seller is unable to deliver clear title, it is likely that the buyer will be unable to obtain title insurance. In that case, the insurance contingency will allow the contract to be canceled.

In addition to contingencies, the seller will make certain warranties to the buyer. Warranties are essentially promises or guarantees.

Common warranties are:

- that the seller is the owner of the property,

- that the seller can transfer clear title to the buyer,

- that all the easements and liens of record are the only liens and easements on the property …and

- that the seller is able to sell the property, and the property is fit for its intended use

Most real estate contracts contain additional provisions, and these will be crafted by the drafter based on the particular transaction.

It's a good idea to list and describe all personal property left behind in the property for the buyer. Personal property and real property are governed by different sets of rules. One of the biggest sources of confusion after a closing is personal property. First, defining personal property is difficult. The buyer will take a narrow definition, including everything possible as part of the real estate. However, the seller will take a broad view, thinking that personal property is not part of the real estate, and was not included in the contract. Furniture is an easy example. Most people would not consider a bed or sofa part of the real estate. So if those were being included in the real estate sale, they would be listed in the additional provisions. But appliances are a different story, as are light fixtures, wall units, and bathroom fixtures. The seller may want to take those with him, and they can be removed without much damage to the house itself. But the buyer may expect those to be included because they're seemingly built into the house. In a dispute in court, the analysis can get very deep. For our purposes here, the lesson is to include as much detail as possible about personal property what is going to stay with the real estate and what is not.

If personal property remains with the real estate, especially air conditioning units, appliances, or electronics, which might still be under warranty, then the transfer of those warranties, should be noted in this section.

The appointment of the closing attorney or title agent can be listed in a number of different places. Some contracts add the appointment in a separate provision rather than mixing it with the closing date. This is depends on local custom.

While the buyer will have an inspection period to formally evaluate the condition of the real estate, there is often an additional provision to the real estate contract that allows the buyer to walk through the property one last time before the closing. The purpose of this provision is to allow the buyer to make sure that nothing has materially changed about the real estate since the inspection. A material change could be grounds to cancel the contract or postpone the closing. A material change could include fire or storm damage, major alteration to the building on the land, willful damage to the property, or anything that would render a warranty made earlier in the contract invalid.

The contract ends with the signatures of each party. If one of the parties is a corporation or other non-human entity, the real estate contract is signed by a duly appointed representative, who will affix the corporate seal of the entity. Sometimes a resolution of the corporation, partnership, or other entity is attached to the real estate contract showing the signer's authority to bind the entity.

But that's not really the end. Most real estate contracts have addenda, or pages added on to the end of the contract. Since real estate contracts in many states are pre-printed forms, the addendum is the place to put specific closing information and other documents. But be careful, in order for the addenda to be considered part of the real estate contract, they have to be referenced somewhere in the real estate contract itself and made a part of the contract by reference.

The most common addendum is the legal description of the subject real estate. The contract itself usually has the address of the property. But the address is not specific enough to craft a deed or perform a title search. The legal description has the metes [pronunciation as the plural for the word “meat”] and bounds describing the borders of the real estate. It's possible that the seller is only selling part of his real estate. That would make the address meaningless. The legal description reflects the property that is subject of the sale. In a typical transaction, the legal description is copied from the seller's deed that he received when he bought the property, and is copied over again to the deed given to the buyer.

Another common addendum is the description of the personal property being transferred as part of the sale. Again, this can be inside the contract, but since most real estate contracts are standard forms, there may not be space for an exhaustive list.

Sometimes a real estate contract will have an escrow agreement addendum. Some states favor having more details written out for the person holding the earnest money deposit describing how to dispose of the money. Also, many escrow agents want a separate document signed by both parties releasing the escrow agent from liability in the event of a dispute.

In commercial real estate contracts, it is common to have an addendum that lists the known easements, restrictions, and liens of record so the buyer knows exactly what they're getting into.

Other attachments to a real estate contract are called amendments. An amendment is a change to a term in the existing real estate contract. For example, one common amendment is the changing of the closing date. That usually happens because banks take longer to approve loans and the closing has to be moved to a later date. Sometimes the closing is moved up when things go smoothly. Sometimes life events just come up and the day has to be changed.

In commercial real estate transactions, there is typically an amendment changing the name of the buyer. Many commercial properties are purchased by single purpose limited liability companies. So, while the contract was signed and negotiated by one company, that company will open a separate limited liability company to hold title to the real estate. This is common for tax and liability purposes.

Amendments and addenda are different although they might sound similar. An addendum provides supplemental information regarding the real estate contract. An amendment actually changes a term of the real estate contract. An amendment must be signed by both parties, just like the real estate contract, while an addendum is a part of the contract and does not need a separate signature.

Key Terms

Addendum

Additional pages of material that are added to and become part of a contract.

29.7 Performance

Transcript

In order to have a valid contract, certain elements must be met. This is true of all contracts, including real estate contracts. There must be parties who are competent to contract. There has to be consideration, meaning, the contract is being fulfilled in exchange for something of value. There must be a meeting of the minds, where both parties understand their obligations and the terms and conditions of the contract. Once all the terms of the contract have been worked out and understood, there must be performance.

Performance is completing the undertaking and conveyance contemplated in the contract. Or in normal words, doing what the contract tells you to do. In a real estate contract, performance means the buyer pays money to the seller and the seller gives a real estate deed to the buyer. Sounds simple, right? Well, a couple of important questions need to be asked:

- Which party performs in what order?

- What happens if one or both parties fail to perform?

These are all questions that must be asked when considering the issue of performance.

In an ideal world, we would like to see, what's called, full performance. In the real estate contract full performance is the completion of a closing. In other words, the bank funding the mortgage loan pays money into the attorney's escrow account then the attorney pays the money to the seller, while at the same time the seller deeds the property to the buyer. Before reaching the closing table, other obligations are fulfilled. These include reviewing title, paying off outstanding liens on the title, and performing an inspection of the property. Every aspect of the contract has to be completed by the obligated party in order to have full performance.

But what happens if the buyer pays and the seller doesn't deliver the deed? Or, what happens if the seller delivers the deed, but the buyer never pays? Or, what if the seller drafts and signs the deed, but never delivers it to the buyer? This is called partial performance. Partial performance is when one party performs their obligations under the contract but the other party does not. It can also refer to a situation where a party to the contract performs some, but not all of their obligations.

Here are some examples.

In a transaction to purchase and sell a commercial building, the buyer and seller have reached the closing table. The buyer was able to obtain financing from the bank and the bank has funded the sale through the closing attorney. The buyer is ready and able to hand over the purchase money for the real estate. The seller is a corporation. The corporation's president has all of the proper corporate documents to show his authority to sign on behalf of the corporation, including the articles of incorporation, the corporate by-laws, and even a resolution from the Board of Directors, signed by the secretary of the corporation, authorizing the president to sign on behalf of the corporation for this specific transaction. At the moment of truth, the president of the corporation signs and hands the deed to the buyer. The closing attorney wires the escrowed closing funds to the seller and the deal is done. Or is it?

In this case, the corporation's president forgot to affix his corporate seal to the deed. The closing attorney did not notice, and went to record the deed as it was. But the deed was rejected by the county real estate clerk's office because the seal was not present. This is a case of partial performance. The buyer performed his duties, but the seller did not perform all of his duties. He signed the deed, accepted the money, and handed over the deed. But because the deed lacked the corporate seal, it's as if the corporation never signed the document.

In another example, the buyer and seller have reached the closing table. This is a cash closing where the buyer will pay over to the seller the full purchase price from his own money without taking a mortgage. The real estate contract calls for a purchase price of $600,000 for the real estate. The seller signs the deed and hands it over to the buyer. But the buyer only hands back $300,000. This is partial performance. The buyer has not completed his obligation to pay the purchase price.

Another scenario that comes up on some occasions is impossibility of performance. Impossibility means that there is no physical way the transaction can be completed. Impossibility does not mean it is impossible because one party does not want to complete the transaction, but rather that it is physically impossible.

In the movie "The Paper Chase" a class example of impossibility was couched in an example of a mistake. A landlord owns a beach house. He does not live there and generally does not know its condition. He rents the beach house to the tenant for the summer. But when the tenant gets to the beach he sees that the beach house has burned down! This is impossibility. The landlord wants to rent out the beach house to the tenant, and the tenant wants to rent the beach house. But due to the fact that the house burned down it's impossible to perform the transaction.

A more common example of impossibility of performance involves the mortgage part of a real estate contract. One contingency that is common in all real estate contracts involves the buyer getting a mortgage. Most real estate contracts stipulate that the buyer will obtain a mortgage with a certain down payment, at a certain percentage rate of interest, and for a given term to repay. This is because the buyer knows how much money he has to put as a down payment, and how much he can afford in monthly payments. Well... we like to think the buyer knows what they can afford. If the buyer is unable to obtain the mortgage at those terms, this becomes a situation of impossibility. Even if the parties want to complete the contract in full performance, they're unable to because of an outside circumstance.

What remedies are available when a contract isn't fully performed? Most remedies for a real estate contract involve the earnest money. Who gets the earnest money usually depends on whose fault it is for not performing. If the seller is at fault, for example if he refuses to sell after signing the contract, the buyer gets the earnest money back. If the buyer refuses to pay or complete the closing, then the seller usually gets the earnest money. But if there is a situation of impossibility, where neither party is at fault, the earnest money generally goes back to the buyer.

In certain situations, there is a remedy called specific performance. This is done by court order, where the judge commands the party refusing to complete the contract to fully perform all of their duties. This remedy is rarely used. In breach of contract cases, courts prefer to put the parties back in the place where they were at the beginning. Forcing the seller to sell the property, or forcing the buyer to buy the property is contrary to this doctrine. But sometimes it is a necessary remedy. If monetary damages are not enough to compensate the party who suffered the breach of contract, and the parties are able to fully perform the contract, specific performance is a viable remedy. Let's look at an example.

A buyer and seller reach the closing table. The buyer hands over the purchase price for the real estate in cash. He needs the property because he's homeless and needs a place to live. Failing to get the property after closing would pose an enormous financial burden on the buyer. But the seller refuses to sign and hand over the deeds to the real estate. The buyer brings the seller to court. The judge may order the seller to complete the transaction by handing over a signed deed.

In another case, the buyer pays part of the purchase price, while the seller signs and delivers the deed to the real estate to the buyer. However, the buyer only pays $300,000 of the $600,000 owed for the property in this case, the judge may order the buyer to hand over the owed amount to the seller and take possession of the deed.

What incentive do real estate contract parties have if they're violating the law and regulations of the state? If one of the parties does not listen to the judge, there could be significant implications. It is possible to imprison people who do not follow court orders. After the judgment is issued but the seller refuses to sell or the buyer refuses to buy, the court will order the sheriff to arrest the person that is violating the court order. These matters are taken very seriously by the court. It's best to fulfill one’s contracts.

Key Terms

Specific Performance

An action to compel performance of an agreement, e.g., sale of land as an alternative to damages or rescission.

29.8 Termination and Discharge

Transcript

In every transaction, we hope the real estate contract goes from signing to closing, where there is full performance by the buyer, seller, and other parties involved, like the mortgage lender, closing attorney, and real estate brokers. At the end of a closing with full performance, the buyer has tendered the purchase price to the seller, and the seller has conveyed the property to buyer by a written deed. Occasionally, real estate contracts are not fully performed. This partial performance can have two results. Either the party (not in compliance) fulfills their duties, voluntarily or by force, or the real estate contract is terminated.

Termination of a contract means that the contract is void, has no legal effect, and the parties no longer have any obligations under the contract. There are a number of reasons termination can occur. In the context of real estate contracts, the reasons include: failure of the buyer to obtain financing from a bank, the property having a significant defect discovered during inspections, or a problem in the title history that cannot be cleared up in a reasonable amount of time.

When the real estate contract is terminated, the parties may go their separate ways and pursue other transactions. But it's very common in real estate contracts to require the buyer to pay an earnest money deposit. The earnest money deposit is usually held by a third party, and serves as security for the buyer performing his end of the bargain. In other words, if the buyer backs out of the transaction for no valid reason, then the earnest money gets turned over to the seller. If the buyer has a valid reason, as contemplated in the real estate contract or state statutes, then the buyer gets the earnest money deposit back. If there's a dispute regarding who gets the earnest money, then the escrow agent (holding the earnest money) deposits the funds with the court in an action called an “interpleader”, and allows the court to resolve the dispute. An example of where an interpleader action may be necessary is if the buyer claims that he cannot get a mortgage that conforms to the terms of the contract, thereby making the payment unaffordable, but the seller claims that the buyer did not make sufficient effort to apply for a mortgage loan, and intentionally tanked the deal.

Contracts can also be terminated by mutual agreement. Sometimes parties decide on their own to pursue other options. Real estate contracts contain terms for mutual agreement to terminate, like the ones mentioned earlier. But there are circumstances where the parties agree to walk away aside from reasons stated in the contract. For example, if the buyer finds a more suitable property at a lower price, while the seller finds a buyer offering a higher price for his property, the parties can simply sign a release document mutually terminating the contract and releasing the other party from their obligations under the contract and for liability.

A real estate contract can terminate by mutual agreement by the passage of time. It is common for offers to purchase residential real estate to come in the form of complete contracts with a time limit for the seller to accept the offer. If the seller does not sign the contract within the allotted time, then the contract is terminated.

Another way to mutually release a contract is through novation. Novation is when a material obligation is changed in a contract, or an entirely new contract is substituted for the original one.

For example, if the seller and buyer have a real estate contract regarding the seller's property at 123 Smith Street, but the seller decides that he does not want to sell that property and instead offers a new property to the buyer...let's call it 500 Jones Street, and the buyer agrees, they can amend their original real estate contract to change the subject property. They may also amend the purchase price and reset the time for inspection of the real estate and the title history. This is a novation….swapping out a material term of the contract. The termination aspect of novation here releases the parties from the obligations of the original contract. The seller is no longer obligated to sell 123 Smith Street and the buyer is no longer obligated to buy this property.

Another version of novation is to change the contract entirely. In a similar circumstance to the one we just described, where the seller offers a new property to the buyer, if the parties want to change all of the other material terms regarding the transaction, it may be simpler to just draft and sign an entirely new contract. Similarly, the original contract is terminated by execution of the new contract, which should make reference to termination of the original contract. The buyer and seller are no longer obligated to complete any of the terms of the old contract, and are only obligated under the new contract.

A contract can also be terminated by operation of law. One remedy available to a party who is aggrieved when the other party fails to fulfill their part of the contract is to file a lawsuit for damages or specific performance. For example, if the seller is ready and willing to sell a parcel of real estate to the buyer pursuant to a written contract, but the buyer does not show up at the closing, and does not pay over the money required pursuant to the contract, then the seller can file a lawsuit against the buyer asking the court to award monetary damages for breach of contract (or specific performance), compelling the buyer to complete the contract. Similarly, if the seller, pursuant to a contract, accepts the money from the buyer, but refuses and fails to give the buyer a deed for the property, the buyer can file a lawsuit against the seller demanding monetary damages, like the return of the purchase money, or specific performance, requiring the seller to sign a deed for the property and transferring title to the buyer.

Usually a party who feels wronged by a breach of contract will file a lawsuit quickly if it's necessary. After all, in most real estate transactions, time is of the essence. Large sums of money are tied up, and every hour a property is off the market, the seller could lose an untold number of sales opportunities. But there are times when the aggrieved party will not take legal action so quickly. If the seller actually wants to keep the property for a while, like in the case of a commercial property where the seller is receiving rent from tenants. There's just no rush to the courthouse. Or perhaps the buyer found another suitable property and is in no rush to sue the seller.

Can a party wait forever to pursue their claim? In short, no. Each state has a statute of limitations, or time limit, on how long a person can wait before filing a lawsuit to assert a legal claim. The statute of limitations on written contracts varies between four and ten years depending on the state. If the claimant waits longer than the statute of limitations allows, their claim is barred, and the contract is terminated by operation of law. A party cannot bring an action after the statute of limitations elapses.

Another way contracts can be terminated by operation of law is bankruptcy. Contracts for the purchase and sale of real estate are considered to be executory contracts under the United States Bankruptcy Code. When a person (or company) files for bankruptcy protection in the bankruptcy court, their assets become property of a bankruptcy estate. The estate is administered by a trustee appointed by the United States government. The trustee's job is to make sure that the bankruptcy debtor's assets are distributed according to the law, and in the most financially advantageous manner. Usually with a real estate purchase and sale agreement, the trustee will cancel the contract, using his powers under the Bankruptcy Code. If the debtor is the buyer, the trustee will not want to use up available cases to add more property to a distressed estate, or allow the debtor to take on even more debt that he cannot pay. In the case of a debtor who is a seller, the trustee may or may not cancel the contract depending on the market value of the property, and whether the trustee determines he can get a better deal elsewhere.

If the trustee takes no action, and the debtor completes the bankruptcy process, then the debtor is discharged and no longer obligated to pay the debts that accumulated before the time the bankruptcy case was filed. In the case of a buyer who was obligated to complete the purchase of real estate pursuant to a real estate contract, this may discharge his obligation to complete the contract. In the case of a seller who is a debtor, most bankruptcy cases result in the debtor losing their real estate. If the real estate is taken from the seller during the bankruptcy case, to pay debts, then obviously the discharge ending the case results in the real estate contract being terminated by operation of law and impossibility.

Key Terms

Novation

The substitution or exchange of a new obligation or contract for an old one by the mutual agreement of the parties.

29.9 Damages

Transcript

With every real estate contract, the hope is that it will reach closing. The buyer will receive title to the real estate from the seller and the seller will get paid the purchase price. Along the way the brokers, real estate agents, and closing attorney will get paid as well. But there are times when a real estate contract is broken. In most circumstances, the termination of the contract is mutual. If the buyer is unable to get financing that's contemplated by the contract, then the real estate contract is terminated by its own terms with the parties going back to their original starting position. Similarly, if a title search reveals a difficult problem with the title history that cannot be immediately resolved, then the contract will terminate and the parties restored to their original position. But there are occasions when a contract is terminated without both parties agreeing to the separation. In those cases, the party aggrieved may sue in court and demand damages from the other party.

There are many different types of damages. Entire books are written about legal damages. Since we're dealing with a contract, the types of damages are limited by law. The two main types of damages recoverable in a contract case are compensatory damages and liquidated damages.

Compensatory damages are meant to compensate the wronged party. It's a monetary award to make the party whole again. The ancient biblical example is if a man's ox gores another ox, the owner of the bad ox has to pay the victim the value of an ox in money. In modern times, the common example is a car accident. If a person hits your car and they're at fault, they pay you the money to put your car back to the way it was. If you're physically injured, they pay you the cost of your medical bills. But if you have emotional scars, and pain and suffering, a victim can get compensatory damages for those things as well. Over the centuries, courts have been able to put a monetary value on pain and suffering.

But in the context of contracts, an aggrieved party cannot get damages for emotional distress. Compensatory damages are limited to money actually lost during a transaction that went bad.

Another type of damages is liquidated damages. In situations where compensatory damages cannot be calculated, a court can award liquidated damages. Liquidated damages are an estimate of the actual damage incurred by the aggrieved party. The estimate is a sum agreed upon by both parties in the contract. In order for liquidated damages to be awarded, there must be a clause written into the contract itself spelling out the amount of liquidated damages, what the damages are meant to cover, and that both parties understand these are liquidated damages.

Compensatory damages and liquidated damages should be distinguished from other types of damages, like punitive damages. Generally, punitive damages are not available in the context of a contract dispute. Those are reserved for tort actions. Damages for pain and suffering, or emotional distress cannot be awarded in a contract dispute. Other tort remedies are also not available. Conversion and unjust enrichment, two things common to a breach of contract dispute, are not available remedies or causes of action. This is because the contract dispute covers these claims.

Certain disputes and remedies are common to sellers in a real estate transaction. Compensatory damages for a seller are only available in unique circumstances. Usually the seller claims damages for a lost or delayed transaction. Those damages can rarely be calculated because they're so speculative. If the seller enters into a real estate contract and takes the property off the market, there is no definitive way to know whether he would have sold the property to someone else and how much that mystery buyer would have paid.

So, compensatory damages are limited to actual damages. This can occur in a couple of circumstances. One example is where the buyer actually damages the property. A buyer and seller entered into a contract for the purchase of raw land. The land was to be used to drilling oil and natural gas. The contract allowed the buyer to enter onto the land and drill for samples to make sure the land was suitable for their needs. The buyer came for his inspection visit with a large drill rig, drilled several holes, and then left the holes open and left. When the buyer canceled the contract, the seller was left with land with holes in it. The seller was forced to sue the buyer for the cost of hiring a contractor to fill in the holes. All the seller could get was those compensatory damages... money to make him whole again (no pun intended).

Another similar example in a residential context, a buyer's engineer was doing an inspection of a residence that was under contract. The engineer wanted to check the foundation of the house, and went down into the basement and into a crawl space. While there, the engineer knocked out a supporting beam causing part of the house to collapse. The lawsuit that followed involved questions of whether the house was already damaged, or the engineer caused the damage. The seller did receive a certain amount of compensatory damages, for the lost value of his house and the cost of repairs.

Compensatory damages are more common if the buyer does not pay the entire purchase price of a property pursuant to a real estate contract. In most closings, the buyer does not receive a deed to the property unless the seller has received the entire purchase price. This is usually done through a bank giving a mortgage loan to the buyer, and the loan money being paid over to the seller. But sometimes owners sell real estate directly to the buyer and allow the buyer to make payments to the seller. This is a form of owner finance. If the buyer does not make all of the payments, the seller is entitled to compensatory damages, or the unpaid amount of the purchase price. These transactions are considered unwise, but they happen.