Chapter 28 - Real Estate Contract Law

Learning Objectives

At the completion of this chapter, students will be able to do the following:

1) Explain the difference between an express and implied contract.

2) Provide at least one example of a bilateral contract.

3) List at least three elements of a valid contract.

4) Describe the difference between a valid, void, and voidable contract.

28.1 Types of Contracts

Transcript

Contracts are at the heart of real estate transactions. At every step of the process, from listing agreements to sales contracts, to promissory notes, to mortgage documents, contracts play a vital role in real estate.

So what is a contract? Simply put, a contract is a legally enforceable promise. We make promises in our lives every day. You might promise a friend to drive her to the airport. Or you might promise to lend your car to a friend, so she can drive herself to the airport. These kinds of promises are not legally enforceable. Your friend can’t go to court and ask the court to make you give her that ride. It’s only an empty, unenforceable promise. A contract’s useful that way. You can ask a court to enforce a contract, and the court will either make the other party perform their obligations under the contract or make them pay you money damages if they don’t.

So what turns a promise into a legally enforceable contract? We’ll talk about the essential elements of a contract later in this chapter. For now, it’s enough to know that two people create a contract when they agree to perform actions for one another and intend to make their agreement legally enforceable.

Let’s take a tour of the types of contracts you’re likely to deal with as a real estate agent. As you’ll see, most real estate contracts involve one person giving money to another in exchange for the transfer of some interest in real property, ranging from a simple option to a full purchase.

Sales Contracts

The first stop on our tour is a sales contract. A sales contract is an agreement in which one person agrees to sell real property to another person, who, in turn, agrees to buy the property at a specified price before a specified date. Sales contracts may include other terms, and they can be complex, but every sales contract will specify a legal description of the property for sale, the exact price the buyer will pay for it, and the date by which the sale must close.

A legal description is different from a property’s mailing address. The legal description must identify the exact parcel for sale. The legal description may be a survey map, a metes and bounds description of the property’s boundaries, or a parcel number from the local land records. Local law determines exactly what is required, but every sales contract will provide a legal description of the property for sale.

In addition to property, price, and closing date, sales contracts often include other provisions that protect the interests of the buyer or seller. Many such provisions give buyers a way to leave the deal. For example, a sales contract may allow a buyer to withdraw from the sale if a home inspection reveals defects in the property, like a bad foundation, or failed water test on a well.

Leases

Our next stop is a lease. A lease is a contract that allows someone to possess and use real property for a specified time. Although we may be most familiar with apartment leases, a lease agreement can apply to any property—a house, a condominium, even empty land.

Like a sales agreement, a lease needs to identify the leased property. However, because a lease is only a temporary transfer of possession, the property description is often less formal. A mailing address might be enough for a lease, but not be sufficient for a sales contract.

The lease must also specify the person who will take possession of the property (known as the lessee), how long they will possess and use the property, and how much rent they will pay in exchange. When the lease ends, possession and use of the property returns to the original owner (known as the lessor).

A lease agreement may include additional clauses, spelling out other obligations for each party. For example, the lease may specify who is responsible for repairs if a pipe bursts or spell out when and how the lesser can enter the leased property during the lease.

Options contracts

The next stop on our tour is an options contract. An options contract gives a party a right—but not an obligation—to purchase a property at a specified price during a specified time. During the options period, the seller cannot sell the property to anyone else. At the end of the options period, if the option holder has not exercised his option, then the seller is free to sell the property to someone else.

Similar to an options contract is a right of first refusal, which gives a person the chance to buy a property before anyone else. For example, if a third party offers to buy the seller’s property, a right of first refusal might require the seller to first offer the property to the rights holder under the same terms. The seller would only be able to sell to the third party if the person holding the right of first refusal refuses the offer.

Listing agreements

Our next stop is listing agreements, which are a real estate agent’s bread and butter—literally. A listing agreement creates an agency relationship between an agent and a seller and authorizes an agent to sell a property on the seller’s behalf. The listing agreement determines how—and whether—a real estate agent is paid.

There are four major types of listing agreements.

An exclusive right to sell listing, as its name implies, gives an agent the exclusive right to sell a property on behalf of the seller. The seller is free to sell the property on her own, but the seller can’t ask another agent to sell the property while the exclusive right to sell agreement is in effect. Moreover, even if the seller sells the property herself, she will still be obligated to pay the agent the agreed fee. With an exclusive listing agreement, if a sale occurs, the agent receives a fee.

An exclusive agency listing gives an agent the exclusive right to sell a property on behalf of the seller, but if the seller sells the property on his or her own, without help from the agent, then the agent is not entitled to a fee. Under an exclusive agency listing, the agent only receives a fee if the agent produces the sale.

An open listing allows the seller to make listing agreements with as many agents as he wishes, and no agent has an exclusive right to sell the property on the seller’s behalf. If the seller sells the property without an agent’s help, then no agent receives a fee. With an open listing, an agent only receives a fee if she is the first agent to produce a sale.

The last type of listing agreement is a net listing agreement. A net listing is notable because it is illegal in many states. In a net listing agreement, the seller specifies how much she wants to receive from the property, and the agent can keep any extra amounts earned from the sale. Many states disfavor net listings because they tend to create a conflict of interest between the seller and the agent. The seller may unknowingly underestimate the value of the property, resulting in an unfair windfall for the agent.

Independent Contractor Agreements

The last stop on our tour of real estate contracts is an independent contractor agreement. Labor laws and tax codes treat people differently, depending on whether they are employees or independent contractors. State and federal laws require employers to withhold payroll taxes from an employee’s compensation. However, a person may be considered an independent contractor if the person controls the manner, place, and time in which they perform their services. Companies are not required to withhold payroll taxes from independent contractor payments, and Independent contractors are responsible for managing their tax responsibilities themselves.

Traditionally, independent contractors show themselves to be independent by demonstrating that they control the time, manner, and place under which they work. Although a company may hire them to perform a particular task, the company generally does not tell them how, when, or where they should do the task. The independent contractor is responsible for getting the job done; how they go about doing that is their business.

Real estate agents may work as employees or as independent contractors, and a brokerage firm and agent usually decide which approach they’ll take when they begin working together. Often, real estate agents only earn a commission or fee if they make a sale, and they receive no other salary. This arrangement looks a lot like an independent contractor arrangement. However, state law usually requires brokerage firms to supervise their agents, and the more a firm supervises its agents, the less the agents look like independent contractors. This legal requirement can make it difficult for real estate agents to pass the traditional test for independent contractor status.

Recognizing this difficulty, state and federal laws carved out special independent contractor rules for real estate agents. For example, the IRS considers a real estate agent to be a “statutory nonemployee” if (1) the agent is licensed, (2) the agent’s fees are based on sales, rather than hours worked, and (3) the agent works under a written agreement that says the agent will not be treated as an employee for federal tax purposes. State law may provide additional requirements, but an independent contractor agreement makes it clear to everyone—the agent, the brokerage firm, and the state and federal tax departments—how the agent’s taxes and payments should be handled.

These are not the only contracts you may come across as a real estate agent, but these are some of the most common.

Express Contracts

Now let’s talk about the difference between express and implied contracts. An express contract is a contract where the parties clearly state all the terms of the agreement, and each party knows what they must do to complete the contract. An express contract may be oral or written and still be enforceable. A contract is an express contract if the parties have expressed all the terms clearly.

Express contracts are common in real estate because a legal requirement known as the statute of frauds requires most real estate contracts to be in writing. In 1677, the English Parliament passed an act stating that, if parties wanted a court to enforce certain kinds of contracts, those contracts would have to be written and would have to be signed by the persons bound by them. This idea has come down to the present day. Every state has a statute of frauds, and all of them require contracts regarding transfers of interests in real property to be committed to writing. There is one important exception to this rule. An oral lease for less than a year is enforceable and does need not be in writing.

Implied Contracts

A contract may also be an implied contract. An implied contract may exist if the circumstances indicate the parties intended to create a contract. Implied contracts may be implied-in-fact or implied-in-law.

For example, suppose Bob has plowed Sally’s drive after snowfall for many years, and each time, Sally has paid Bob a certain amount, even though Bob never sent her a bill. If a snowstorm struck again, and Bob plowed Sally’s drive, but she refused to pay, a court might find an implied-in-fact contract, based on Bob and Sally’s long-standing behavior. If so, the court would require Sally to pay Bob for plowing.

An implied-in-law contract exists when failing to find a contract would be contrary to law. Imagine Sally gave Bob a diamond ring and asked him to keep it and give it to her children when she died. Without agreeing to Sally’s request, Bob takes the ring from Sally, sells it, and uses the money for himself. If Sally died, and her children asked Bob to return the ring, a court might find a contract implied-in-law because not finding a contract would unjustly enrich Bob at the expense of Sally’s children.

You may have guessed it isn’t easy to convince a court to enforce an implied contract, and you’d be right. Implied contracts usually only arise when essential elements of an express contract are missing—terms haven’t been clearly expressed, or no written agreement exists, or the parties disagree about what was said. Under these circumstances, courts are generally reluctant to find that a contract exists. As a result, it’s generally unwise to rely on implied contracts. Express contracts—in writing—are usually the wisest course.

Because implied contracts usually are only an issue when there is no written contract, they are rare in real estate, because the statute of frauds requires almost all real estate contracts to be in writing.

Bilateral contracts

Let's finish this lesson by talking about the difference between bilateral and unilateral contracts. A bilateral contract exists when a contract places obligations on both parties. When we think of a contract, we're usually thinking of a bilateral contract. Imagine that Bob agrees to sell Sally his watch in exchange for $100, and she agrees to buy it. Both Bob and Sally have obligations under the contract. Bob must give Sally his watch, and in exchange, she must give him $100. If either party refuses to perform his or her obligation under the contract, the other party could sue to enforce the contract.

Bilateral contracts are common in real estate. For example, sales contracts are bilateral agreements. The seller promises to provide clear and marketable title of the property to the buyer by a certain date, and the buyer agrees to provide a specified sum. The contract requires both parties to perform.

A lease agreement is also a bilateral contract. The lessor agrees to surrender possession and use of property for a specified period, and the lessee agrees to pay a specified rent for using and possessing the land during the lease period. The contract obliges both parties to perform.

Most listing agreements are also bilateral. The seller gives the agent the right to sell a property on the seller’s behalf and agrees to pay the agent a fee if the agent produces a sale. In exchange, the agent agrees to use her knowledge and expertise to sell the property for the seller.

Even an independent contractor agreement is a bilateral agreement between the agent and the brokerage firm. The agent acknowledges he is an independent contractor and agrees to maintain his license, follow the state laws and rules for real estate agents, and try to sell properties. For its part, the brokerage agrees to pay the agent commissions and fees on the agent's sales and to not treat the agent as an employee for federal tax purposes. Both parties have obligations under the contract.

Unilateral Contracts

A contract does not have to be bilateral to be enforceable. Some unilateral contracts are enforceable as well. A unilateral contract is a contract where only one party is bound to perform. Suppose, for example, that Bob loses his cat, and posts flyers around the neighborhood that read, “If you find my lost cat, and I will pay you a $50 reward.” Many people walk past the flyer. Some even stop and read it, but none of them makes an effort to find the cat. Sally, however, stops to read the sign and realizes she has seen Bob’s cat near her house. She rushes home, recovers the cat, and takes it to Bob. Does Bob have to pay her the $50 reward?

Bob’s flyer is a unilateral contract—a one-sided contract—because only Bob is required to perform under the contract. The people who stopped to read the flyer were not obligated to do anything. Sally was not obligated to return the cat, even though she knew where it was. Whether Sally chose to participate was entirely up to her. However, Bob is obligated to pay the $50 reward to anyone who shows up on his doorstep with his cat. Once a party stepped forward with his cat, Bob’s unilateral contract obliged him to pay the reward.

Unilateral contracts occur in real estate most often as open listings. Remember, an open listing is a listing agreement in which the seller agrees to pay a commission or fee to any agent who sells the seller’s property. No agent is obligated to try to sell the property, but if they do sell it, then the seller is obligated to pay the stated fee. Open listings are unilateral contracts that create an obligation solely for the seller, and create no obligation on the part of an agent.

In the next lesson, we'll talk about the legal effects of contracts.

Key Terms

Bilateral Contract

A contract in which each party promises to do something.

Contract

An agreement to do or not to do a certain thing.

Express Contract

A contract that has been put into words, either spoken or written.

Implied Contract

An agreement that has not been put into words, but is implied by the actions of the parties.

Statute of Frauds

A state law, based on an old English statute, requiring certain contracts to be in writing and signed before they will be enforceable at law, e.g.. contracts for the sale of real property, contracts that are not performed within one year.

Unilateral Contract

A contract in which one party promises to do something if the other party performs a certain act, but the other party does not promise to perform it; the contract is formed only if the other party does perform the requested act.

28.1a Types of Contracts Infographic

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the Infographic below.

28.2 Essential Elements of a Valid Contract

Transcript

INTRODUCTION TO THE ESSENTIAL ELEMENTS OF A VALID CONTRACT

In the last lesson, we talked about some of the contracts you’re likely to come across as a real estate agent. As you’ll recall, we said that two people create a contract when they agree to perform actions for one another and they intend to make their agreement legally enforceable.

In this lesson, we’re going to go further and talk about the essential elements of a contract. By the end of the lesson, you’ll have a better understanding of what it takes to make a contract.

Why should you care about contracts as a real estate agent? Isn’t that the lawyer’s job? Yes and no. As a real estate agent, you’ll handle contracts often, and you'll want to make sure every transaction you work on finishes smoothly. Understanding what makes a contract valid and enforceable, and understanding how the contract negotiation process works, can help you clear up confusion between the parties that could potentially become a “road block”, which sometimes will even stop the sale in its tracks.

So what are the essential elements of a legally enforceable contract? You may hear people divide the essential elements of contract in a variety of ways—three elements, five elements, seven elements. Don’t be confused when you see this. You can slice the contract pie up into many pieces, but in the end, it’s all the same pie. When you look closely at the conversations about contract elements, you’ll find they all cover the same ground.

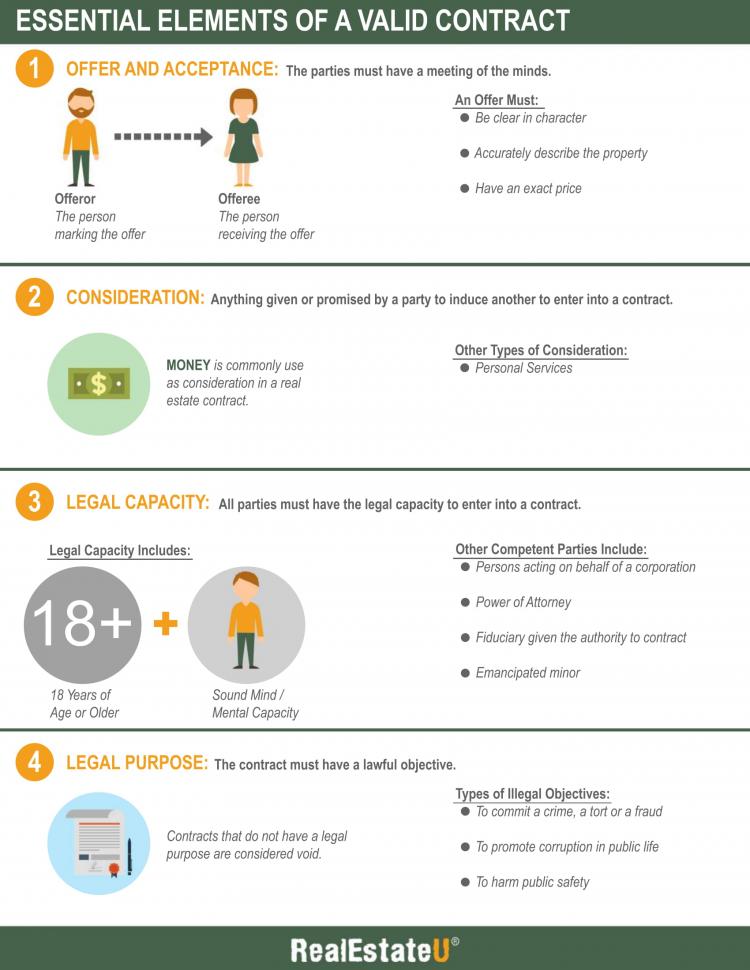

For our purposes, we’re going to break the contract elements up into four pieces: (1) offer and acceptance, (2) consideration, (3) legal capacity, and (4) legal purpose. If these phrases sound intimidating, fear not. These are just legal terms for straightforward, everyday concepts. I’m sure you’ll find them familiar as we talk about them because most of these ideas come from common sense and common experience.

OFFER AND ACCEPTANCE

We’ll talk about offer and acceptance first because offer and acceptance lies at the heart of making a contract. Bargaining between two people is the primary engine driving a valid contract. As the phrase implies, you have offer and acceptance, in other words someone makes a clear offer and another person accepts it.

Ideally, the offer should make the most important terms of the offer clear enough for the other person to accept just by saying, “Yes, I agree.” A simple example makes this concept easy to understand. Suppose I said to you, “Would you like to buy my watch?” If you were interested, your first question would probably be, “Maybe. How much do you want for it?” You aren’t likely to say, “Yes,” until you know what I want in exchange. My offer wasn’t clear enough because you needed more information to decide whether to accept.

When I ask, “Would you like to buy my watch?” I am inviting you to bargain with me, not making you an offer. Lawyers call this “an invitation to treat.” It means, “Hey, can we make a deal here?”

To be more than an invitation to treat, an offer needs to lay out all the terms the other party would need to know to say, “Yes.” An offer does not have to be complicated. “I’ll sell you my watch right now for $100” sums up a clear offer nicely. The offer specifies the item for sale, the price to be paid, and the time and manner of delivery—all the basic terms of a contract for sale of personal property like a watch. The other person only has to say, “Sure. Here’s my $100,” and the two parties have a contract. That is clear, straightforward offer and acceptance.

But in real estate transactions, offers are rarely that simple. When buying property, the buyer and seller need to work out many terms, and many of those terms are conditional. Will the buyer be able to get financing? Can the seller convey clear and marketable title to the property? Will the home inspection reveal defects that spoil the deal for the buyer? Will the title opinion reveal permitting violations or delinquent tax issues that need to be resolved? Because of these more complicated issues, real estate contracts tend to be more complex than the sale of personal property like watches, cups of coffee, or bookshelves. But the essential idea remains the same: the essential terms of the offer must be clear enough for the other party to say, “Yes.”

The offer must also be sincere. The person making the offer must intend the offer to become a legally binding contract. An offer made in jest cannot create a contract.

Let’s turn to acceptance. So far, we’ve imagined that the person receiving the offer only has to say “Yes” to create a contract. This is the ideal case. But what if the person receiving the offer says something other than “Yes”? What happens then?

Imagine Suzy wants to sell her house to Leopold for $300,000 with a closing on May 13. She really wants Leopold to just say ”Yes,” so she draws up a detailed sales contract and writes all the conditional clauses to lean in Leopold’s favor. Because she’s made the agreement so favorable to Leopold, Suzy believes she’s making Leopold an offer he can’t refuse.

Leopold reads the sale contract, and says, “No, thanks.” Do Suzy and Leopold have a contract? Of course not! Suzy made an offer. Leopold did not accept it; in fact, he rejected the offer outright.

Offer without acceptance does not make a contract!

But suppose Leopold had said, “Sure, Suzy. I like what you’ve done here. This is a nice agreement. You’ve got a deal. I’ll pay you $280,000 and we’ll close on May 14.” Do Suzy and Leopold have a contract now?

No. They don’t. Leopold changed the terms of Suzy’s offer. He agreed to pay $280,000 instead of $300,000 and he moved the closing date from May 13 to May 14. This is not what Suzy offered. Leopold’s response failed what lawyers call the “mirror image” rule. The mirror image rule says the terms of an acceptance have to mirror the terms of the original offer.

If a response doesn’t mirror the original offer, the law considers Leopold’s response a rejection of Suzy’s original offer and a counteroffer that Suzy can now accept or reject as she wishes. Suzy’s original offer is now dead, but a new offer is up for consideration. Leopold’s new offer incorporates all the terms in Suzy’s sales contract, but changes the price to $280,000 and changes the closing date to May 14. Suzy is now in a position to accept or reject Leopold's offer. She can say “Yes” and Suzy and Leopold will have a contract, or she can reject the offer by saying, “No,” or by making a counteroffer of her own. This process will continue until one party makes an offer to which the other party simply responds, “Yes.” With a simple, unqualified, “yes,” the parties complete offer and acceptance.

These actions—offer, counteroffer, acceptance, rejection—make up the heart of contract negotiation. The more negotiated a contract is, the clearer the parties are likely to be about what is expected of them, and the happier the parties are likely to be with their resulting bargain. Negotiation and bargaining increases the chance that the parties have considered and resolved the most important terms of their contract. The law values the way bargaining clarifies the parties’ positions and expectations, and the more heavily negotiated an agreement is, the more likely a court is to recognize the agreement as a binding contract.

Real estate sales often involve extended negotiation, and parties often toss offers and counteroffers back and forth to one another. Many times, you will find yourself directly involved in communicating offers or counteroffers between your client and the other party. Sometimes, the negotiation process can become messy, and parties can wind up talking past one another about different things.

For this reason, when you are participating in negotiations, be sure you understand exactly what each party is proposing in an offer or counteroffer. If you are ever uncertain what a party is proposing, take the time to ask them explicitly and clear up the confusion. Uncertainty during the bargaining process can kill a contract at the closing table, if parties realize they have been talking about two different agreements. Drafting the written agreements usually reveals these sorts of confusions, but if you can prevent the confusion from occurring at the talking stage, you can make the drafting stage go more smoothly, and increase the chances of the deal closing happily for everyone.

Sometimes, an offer will specify a method for acceptance. When the offer specifies a method of acceptance, the person accepting the offer must use the specified method, or a binding contract will not form. For example, imagine an offer says, “Send your acceptance in writing to our office by 12:00 p.m. on Tuesday.” A phone call to the office at 11:00 a.m. or a written acceptance delivered at 1:00 p.m. will not create a binding contract because the acceptance didn’t meet the requirements in the offer. Of course, the person who made the offer may overlook the late acceptance and still agree to make a binding contract. In that case, the original offer dies, and the improper acceptance is a counteroffer, which the first party accepts. Case law is full of arguments about whether an acceptance was sufficient. The safest course is to follow any specified acceptance methods to the letter. If the prescribed method is impossible for some reason, then resolving the issue with the other party before the acceptance deadline is the next best course.

However, an offer cannot use silence as acceptance. A party cannot bind another person by saying, “If I don’t hear back from you, then I consider this a binding contract.” Acceptance must be clear and affirmative.

This requirement for a clear and affirmative acceptance flows from an important bedrock of contract law. The law requires parties to agree freely and mutually to a contract. Fraud, coercion, or mistake about the terms of a contract may make the contract unenforceable because, in these cases, one or both of the parties did not freely agree to take on the duties required by the contract. The bargaining process helps make sure the parties to a contract freely and mutually agree to their deal.

CONSIDERATION

The second essential element of contract is consideration. Consideration represents things of value that the parties exchange with one another as part of the contract. If I do this valuable thing, then you will do that valuable thing. Consideration sets a contract apart from a promise or a gift.

Let’s look at a concrete example of consideration in action. Suppose I said to you, “I’m going to give you my watch someday, for free.” Even if you replied, “OK,” consideration would not exist because I haven’t asked you to do anything in exchange for the watch. All you can do is wait patiently and hope that one day I give you my watch. Without consideration, my offer to give you the watch is an unenforceable promise.

The situation changes if I say to you, “Look, if you give me $100, I’ll give you my watch right now.” If you agree to this offer, then consideration clearly exists. I will give you my watch, and you will give me $100. We both receive something of value, and your parting with $100 obliges me to part with my watch.

Consideration can be anything of value that a person does or gives, including personal services. Think back to the exclusive right to sell agreements from last lesson. In those agreements, a seller gives an agent the exclusive right to sell a property, and agrees to pay the agent a fee if the property sells, even if the seller—not the agent—finds the buyer. In that case, what consideration does the agent provide? Can’t the agent just sit back and wait for the seller to sell the house?

No. Remember, the duty to perform in good faith requires the agent to try to sell the property, and the agent’s efforts to sell the property are the consideration provided by the agent. The seller is counting on the agent’s expertise, experience, and skill to find a buyer for the seller’s property, and sometimes sellers leave the sales effort entirely in the agent’s hands. For these sellers, the agent’s personal services for the seller are valuable indeed. Personal services can be consideration for a contract.

Consideration can also be an agreement not to do something. For example, imagine that Larry has a splendid view from his south window, looking out across Henrietta’s property, which features an uninterrupted expanse of an attractive mountain ridge rising from the edge of a large poppy field. Because Larry loves the view, he offers Henrietta $5,000 if she’ll agree not to build anything in the poppy field. Larry doesn’t want her to maintain the poppy field. He doesn’t care if the poppy field fills up with trees and shrubs. He just wants to see a natural view from his south window, with the mountain ridge rising in the distance. Henrietta accepts Larry’s offer.

What’s the consideration here? Henrietta doesn’t have to do anything to collect $5,000. She can sit with Larry and watch her field fill up with weeds, or she can travel the world and ignore her property altogether. Either way, Larry will give her $5,000. But the law sees consideration here because Henrietta is giving up something valuable. She’s giving up the legal right to build on her property. If not for the contract, Henrietta could build anything in her field—a garden shed, an outhouse, a gargantuan stone tower. By making a contract with Larry, Henrietta gives up all those opportunities. Seen from this point of view, both parties are providing valuable consideration: Larry is giving up $5,000, and Henrietta is giving up the opportunity to put buildings on her open field.

Sometimes lawyers call this idea of giving up a legal right the legal detriment test for consideration. Under the legal detriment test, consideration exists if a party agrees to do something they are not legally obligated to do or agrees not to do something they have a legal right to do. By making the agreement, the party limits their legal rights in some way.

It follows from the legal detriment test that if you agree to do something the law already requires, then consideration can’t exist. A classic example can clarify this idea.

Imagine Phil has a 15-year-old nephew named Brian. Phil promises Brian he will pay him $500 if Brian does not smoke until his eighteenth birthday. Brian dutifully refrains from smoking, and on his eighteenth birthday, Brian rushes to Uncle Phil and asks him for the $500 he promised. Phil takes his pipe from his mouth and tells Brian he owes Brian nothing because state law says minors can’t smoke. Because the law already required Brian to refrain from smoking, his admirable restraint could not be consideration for the contract. Poor Brian had to skip the $500 and settle instead for heathy lungs and a lesson learned.

Using an idea similar to the legal detriment test, courts often say that consideration must be bargained-for. In other words, each party must agree to perform their actions under the contract because of the contract. This idea focuses on whether the parties actually bargained for the obligation they are undertaking. If the parties would have performed the actions anyway, without the contract, then courts may not find consideration in those actions. Past actions usually can’t serve as consideration for a contract under this view because the past actions were not bargained-for during negotiation. Some new, bargained-for action is required to create consideration.

Finally, I should note that U.S. courts today generally do not consider love and affection to be sufficient consideration to support a contract, even though love and affection are undeniably valuable. There are other countries and other legal traditions where love and affection is sufficient consideration for a contract, but for the most part, U.S. courts will not consider it sufficient.

LEGALLY COMPETENT PARTIES

In addition to consideration and offer and acceptance, a contract must involve parties with the legal capacity to make a contract. Sometimes we call this idea legal competence. A party has the legal capacity to make a contract if they can understand the legal consequences of what they are doing.

The legal capacity requirement tries, in part, to make sure that parties accept their obligations under the contract freely and willfully. If a person doesn’t understand that they are entering a legally binding contract and that the contract will require them to perform certain obligations, how can we say the person freely “accepts” the terms of the contract? To avoid this, courts will not hold a person legally responsible for obligations under a contract if they could not understand what they were doing when they made the contract.

Legal capacity usually isn’t an issue because the law presumes that every adult has the legal capacity to enter a contract. Legal capacity does not present a very high bar, and a party’s actual understanding of what they are doing is not the test.

However, the court will not apply the presumption to certain categories of people, namely, legal minors, mentally ill persons, and intoxicated persons. The law recognizes that experiences like immaturity, inexperience, mental illness, or intoxication can limit a person’s judgment and that other people might take unfair advantage of that limited judgment. As a result, the law treats people in these categories a little differently when it comes to contracts.

We’ll cover this issue more fully in the next lesson, but here’s the short version. If a party to a contract lacks legal capacity due to minority, mental illness, or intoxication, a court may still enforce the contract, but the contract will be voidable, meaning that the party lacking legal capacity gets to choose whether to go ahead with the contract or void it. If he or she decides to void the contract, then neither party will have to perform obligations under the contract. However, if the person lacking capacity chooses to proceed with the contract, then the other party must perform.

As I said, legal capacity usually isn’t an issue because the court presumes that adults have the legal capacity to make a contract. However, you definitely should remember the concepts of legal capacity and voidable contracts if a 15-year-old approaches you and wants to sell the mansion he inherited from his parents who died in a plane crash. Any listing or sales contract you make with him is likely to be voidable by him until he turns 18.

LEGALITY OF OBJECT

So far, we’ve talked about offer and acceptance, consideration, and legal capacity. In addition to these essential elements, a contract must also have a legal purpose. Courts will not enforce a contract that aims to accomplish something that is illegal. Nor will they enforce a contract that is against public policy.

Imagine Sally wants to take out a contract on her neighbor Jan. She hires Bill to be the hitman. Sally and Bill bargain extensively, working out the details. Eventually, they agree that Bill should kill Jan on a particular Friday because Sally will be out of town that day, giving Sally a solid alibi. Sally promises to pay Bill $100,000—after the killing. Bill follows Sally’s instructions exactly, but when Sally returns to town and Bill asks for payment, Sally refuses to pay him. Instead, she smiles sweetly and says, “Sue me.”

Let’s run through our checklist. Bill and Suzy both have the legal capacity to contract. They bargained for their agreement, coming to terms after a process of offer, counteroffer, and acceptance. Consideration clearly exists because Bill agreed to perform a very personal service for Sally, and Sally agreed to pay Bill $100,000. Based on our discussion so far, Bill and Sally would seem to have all the essential elements of a valid contract. However, Bill is not going to be able to ask a court to make Sally pay because the courts will not enforce a contract with an illegal purpose. Killing a person for money is decidedly not a legal purpose. Hitmen do not get to go to court to enforce their contracts.

The history of real estate transactions provides another useful example of illegal purpose. In the last two centuries, property owners in the Unites States would sometimes make agreements with one another not to sell their properties to persons of certain races or ethnicities. In 1948, the United States Supreme Court decided in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 US 1 (1948) that these restrictive covenants were legally unenforceable because they violate the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution.

However, despite the Shelby ruling, discriminatory sales persisted because owners tried to enforce the covenants privately, without court involvement. In 1968, the United States Congress enacted the Fair Housing Act, or FHA. The FHA says it is unlawful to refuse to sell, rent, or lease property to a person based on the person’s race, color, religion, national origin, sex, disability, or familial status. Because the FHA makes discriminatory sales illegal, courts will not enforce a contract that attempts to restrict the sale, rent, or leasing of property based on these characteristics.

IN-WRITING (STATUTE OF FRAUDS)

A contract can fail due to illegal purposes less sinister than murder or discrimination. You will recall from the previous lesson that every state has enacted a law called the statute of frauds, based on an old English statute of the same name. Both the old and the new statute of frauds say that a contract conveying an interest in real property must be in writing. If contracts concerning real estate aren’t in writing, then courts will not enforce them. (The sole exception to the writing requirement is a lease lasting less than a year.)

The statute of frauds serves at least two important public policy purposes. First, requiring real estate contracts to be in writing makes contracting parties think more carefully about what they are doing. Writing an agreement makes the parties more cautious and deliberate, producing more thoughtful negotiations than might occur with an oral contract. Second, the statute of frauds produces a handy evidentiary record of the parties’ agreement. A written contract protects against loss of memory and minimizes disagreement between the parties regarding their agreement.

In the next lesson, we’ll talk about what happens after the parties reach a valid contract and start to perform their obligations.

Key Terms

Consideration

Anything given or promised by a party to induce another to enter into a contract, such as money, personal services, or a promise not to do something.

Statute of Frauds

A state law, based on an old English statute, requiring certain contracts to be in writing and signed before they will be enforceable at law.

28.2a Essential Elements of a Valid Contract Infographic

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the Infographic below.

28.3 Legal Effects of Contracts

Transcript

INTRODUCTION TO THE LEGAL EFFECTS OF CONTRACTS

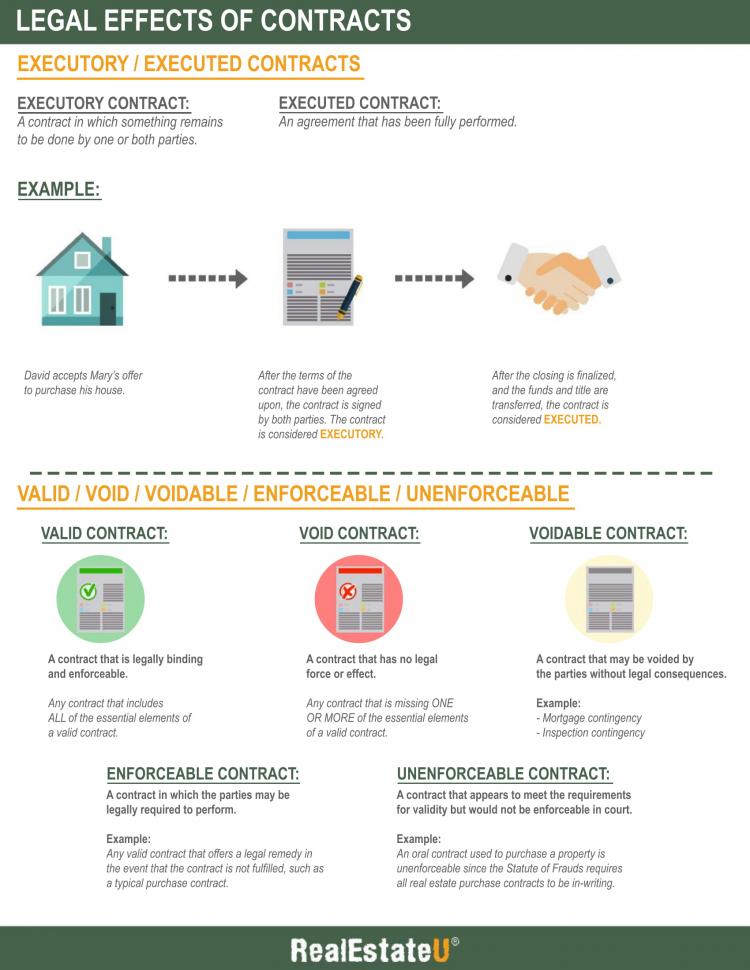

Last lesson, when we talked about contract elements, we assumed that an agreement that had all the essential elements would be a valid and enforceable contract. But that’s not quite the whole truth. Some contracts that appear to be technically valid are not enforceable and have no legal effect. In this lesson, we’ll talk about the legal effects of valid contracts, and how contracts can become void and unenforceable.

Let’s start with a story. Imagine Tanya and Terry make a deal. Tanya offers to sell Terry her house for $200,000. Terry tells Tanya he needs to borrow money to pay for it, and he’s worried he might not qualify for a loan. He’s also concerned about the old furnace in the basement, which doesn’t work well. Tanya agrees to give Terry time to find financing, and if he can’t find a loan, she’ll let him out of the deal. In the meantime, she agrees to replace the furnace. Terry agrees. They set July 1st for a closing date, draw up a purchase and sale agreement, and sign it.

Okay. Tanya and Terry have a contract. But just what does that mean? What’s the legal effect of having a contract?

DUTY TO PERFORM IN GOOD FAITH

First, Tanya and Terry owe one another a duty to perform their obligations under the contract. Terry promised to seek financing so he can pay Tanya $200,000. Tanya promised to replace the run-down furnace. They also agreed to close on July 1st, which means each of them have tasks to perform in order to be ready by closing day. Terry has to find a $200,000 loan, and Tanya has to replace the furnace. If either of them fails to perform, then they can’t close on July 1st.

Before they made their contract, Terry and Tanya owed one another nothing. Either could have walked away from the deal without any consequences. They had no obligation to one another and no reasonable expectation of receiving any benefit from the proposed deal. Without that contract, Tanya’s hope of raising $200,000 from the sale was just a dream, and Terry’s daydreams about a home with a warm, new furnace were just idle fantasies. Making a contract changed Terry’s and Tanya’s hopes and dreams into reasonable expectations of getting either a house or $200,000. The contract now binds Terry to Tanya, and Tanya to Terry, and each has the right to expect that the other will perform the promises made.

The law calls this mutual obligation a duty of good faith and fair dealing. The law expects Tanya and Terry to work in good faith to perform the contract. If Terry doesn’t submit a single loan application, then he is failing to perform in good faith. If Tanya doesn’t replace the furnace before July 1, or she goes down to the basement and spray paints the old furnace to make it look new, then she is failing to perform in good faith.

The duty of good faith and fair dealing is intuitive. Tanya expects Terry to make a good faith effort to secure financing, and Terry expects Tanya to replace the furnace. If you were in either of their shoes, wouldn’t you? When a person doesn’t even try to perform their end of a bargain, we naturally feel the other party has behaved wrongly. Courts feel the same way. If asked, courts are likely to rule for a party who performs in good faith and rule against a party who performs in bad faith.

In the overwhelming majority of cases, parties to a contract perform as expected, and the contract completes without a hitch. It’s not a mystery as to why. In most instances, both parties want to perform their obligations under the contract because each believes they are getting the better end of the deal.

If Terry did not want to pay $200,000 for the house, then he would not have agreed to buy it. Similarly, Tanya must prefer $200,000 in cash to keeping her house. The possible reasons for why Terry and Tanya feel as they do are as varied as human experience can provide. Perhaps Terry has been living in an apartment next to a drummer, and he relishes the peace and quiet that Tanya’s home provides. Maybe Tanya has decided she’s tired of living in one place, and she wants to sell her house and travel the world. The possibilities are endless. The bottom line is that each party to a contract, for their own reasons, believes he or she will be better off if the deal happens. A belief that a deal is in your own best interest creates a natural pressure to perform.

COURT INVOLVEMENT: INTERPRETATION

But not every contract goes smoothly. Sometimes, the parties disagree about what the contract requires. Other times, one party believes the other has failed to perform his or her obligations under the contract. We call a failure to perform a breach of contract. When parties disagree about a contract’s meaning or believe a breach has occurred, courts can help resolve the dispute, if the parties ask for help.

Court involvement is another important legal effect of a contract. If the parties believe they have a contract, then either party can bring a legal action to court, asking the court to interpret or enforce the contract. The court will hear the dispute and help the parties resolve it.

You might wonder why a court would have to interpret a contract. When we talked about the essential elements of a contract, we said that an offer had to be clear enough for another party to accept the terms of the offer. If the parties have made the essential terms of the contract clear, what’s left to interpret?

When you stop to think about it, it’s easy to understand. Parties don’t plan for every eventuality. Let’s go back to Tanya and Terry. Imagine Terry tried to find a loan, but the only loan he could get was at an interest rate five percentage points above the going rate for mortgage loans. Frustrated by the above-market rate of his loan, he tells Tanya that the deal is off because he can’t find financing with a good rate. What will Tanya do?

Tanya might say to Terry, “Hey, we agreed that you could only get out of the sale if you couldn’t find financing. But you did find financing. You just don’t like the rate you got. You’re obligated to take that loan and close on the deal. I’m not letting you out of our contract.”

Terry might reply, “When we agreed on the financing condition, we were obviously talking about a reasonable loan. Surely you don’t mean I have to take any loan available, even if the interest rate is absurd!”

Who’s right? As you can see, they both have a point. Should Tanya be able to force him to borrow money at such a high rate?

This kind of uncertainty can easily arise in any contract, particularly when the parties overlook things that might happen. When Terry and Tanya were talking about financing, their top concern might have been whether Terry would qualify for a loan at all. The possibility that Terry might qualify for a loan that Terry found unacceptable might not have crossed their minds. In situations like these, the parties may call upon a court to interpret the contract, and the court will try to fill in the gaps that the parties had not expressly addressed.

COURT INVOLVEMENT: ENFORCEMENT

A court’s ability to enforce a contract is another important legal effect of having one. It is a major reason people make contracts. Knowing that if your contracting party fails to perform, you can ask a court to enforce the contract is comforting. A court can enforce a contract in two major ways: by awarding money damages or by ordering specific performance.

In most enforcement actions, the court awards expectation damages. An expectation damages award is a money award that puts the non-breaching party in the same financial position she would have been in if her expectations had been met, that is, if the breaching party had performed as promised.

Suppose Terry breached his contract by failing to seek financing, and Tanya sold the house to someone else for $180,000. If Terry had performed as he promised, Tanya would have gained $200,000 from the sale of her house. From Tanya’s point of view, Terry’s breach caused her to lose $20,000. The sale of her house brought her $20,000 less than she expected, based on her deal with Terry. Tanya could sue Terry and ask the court to award her $20,000 in damages, which would place her in the same financial position she would have been if Terry had performed. Her expectations of receiving $200,000 from the sale of her house would then be met. Although a court awards other kinds of relief in a contract case, expectation damages are the beating heart of contract actions, and the goal of the court is to make sure that the non-breaching party gets the expected benefit of the contract.

Sometimes, though, money damages are not enough to compensate a person for the breach. Cases involving real estate are like this. No piece of land or house is exactly like another, and although the seller may have only been seeking money, the buyer wanted to own that specific property. Sales contracts for other unique items like art, custom objects, or items in short supply are also situations where money damages might not be sufficient to meet a party’s expectations from the contract. In these cases, the court may grant specific performance, which is a court order directing a party to do specifically what is required by the contract. If Tanya announced at closing that she had changed her mind about traveling the world and refused to sell, even though Terry had brought the money to closing, Terry could ask the court for specific performance and require Tanya to complete the sale.

VALID CONTRACTS

So far, we have been talking about the legal effects of a valid and enforceable contract. A valid contract is a contract that has all the essential elements of a contract: competent parties, offer and acceptance, consideration, mutual agreement, intent to create legal obligations, and a legal purpose. If an apparently valid contract is unenforceable, it’s usually because it’s missing one of these elements. Once a valid contract goes into effect, the law imposes the duty to perform in good faith and the courts can interpret or enforce the contract, if the parties ask it to.

EXECUTED AND EXECUTORY CONTRACTS

What happens when the parties have completed all their obligations? Does the contract have any further legal effect? The answer is usually, “no.”

When both parties have completely performed their contractual obligations, we call their contract an executed contract. The court will not impose any legal obligations on a party to an executed contract because the parties have already done everything the contract required. The court cannot require them to do more. Executed contract is easy to remember because it sounds like the contract has had its head chopped off, which it has, in effect. The courts will no longer enforce an executed contract because the parties have fulfilled all their contractual obligations.

However, if the parties do have significant obligations left to perform under a contract, then we call the contract an executory contract. Now “executory contract” is not as easy to remember as “executed contract.” Executory just doesn’t have the same ring as executed. But to help you remember, I’ll say it again: an executory contract is a contract in which one or both parties have not yet completed performance of their obligations.

Usually, it’s easy to recognize executed contracts and executory contracts. But sometimes, particularly in real estate, it might be harder to make the right distinction.

Let’s add a fact to Tanya and Terry’s story. Imagine that Tanya has a mortgage of her own with XYZ Bank, and she still owes $120,000. As part of their contract, Terry and Tanya agree Tanya will pay off her loan from the proceeds of the sale and have XYZ Bank record a discharge of her mortgage deed in the land records.

Closing goes off without a hitch. Terry has found $200,000 and Tanya has replaced the furnace in the basement. Terry gives Tanya $200,000. She writes a $120,000 check to XYZ Bank, keeps $80,000 for her, and gives Terry a deed. Are they done? They would seem to be. Terry has a deed, Tanya has $80,000 for her world travels, and XYZ Bank is paid. Everyone’s happy. What else is there to do?

Well, Tanya still has to get XYZ Bank to discharge the mortgage. If XYZ Bank doesn’t record Tanya’s mortgage discharge, then it’s going to cause headaches if Terry tries to refinance or sell the house because Tanya’s mortgage will still show as valid in the land records. Tanya and Terry’s contract is still executory because the mortgage discharge has not been recorded. After XYZ Bank records the mortgage discharge, Tanya and Terry’s contract is an executed contract. They no longer have any legal obligation to one another. Terry can move in, and Tanya can travel.

Let’s talk now about void contracts, voidable contracts, and unenforceable contracts. These contracts have characteristics that render them either entirely unenforceable, or only partially enforceable.

VOID CONTRACTS

A void contract is an agreement that has no force or effect and is legally unenforceable. An agreement can become a void contract in two ways: it can be void when the parties make it or it can become void when something happens to render it void.

Let’s start with the first case—an agreement that’s void when it’s made. A contract is usually void because it lacks some essential element. For example, a contract can be void because it has an illegal purpose. One common example is an agreement between a supplier and a dealer to provide illegal drugs. The supplier and dealer may have bargained extensively to reach a deal beneficial to both of them. They may even have an exquisite delivery schedule mapped out, and thought of all sorts of contingencies for compensating one another if things go wrong. But as a matter of law and public policy, the courts simply will not enforce the illegal drug supply agreement, regardless of how well negotiated it was. The agreement is considered void the moment it was created, because it is created for an illegal purpose. Remember our hit man from the last lesson? His contract, too, failed because it aimed to perform an illegal purpose.

An illegal purpose can be a little harder to see, yet still render a contract void. Imagine Tanya was a renter. She didn’t own the house, but she offered to sell it to Terry anyway. In this case, the agreement between Terry and Tanya would be void when they made it because it’s not legal to sell someone else’s property without their permission. If Terry tried to sue Tanya for breach of contract, the court would not enforce the contract or award damages because the agreement was a void contract. Now, Terry might have a separate fraud claim against Tanya, but that’s another story.

An otherwise valid contract can also become void because of a change in law or circumstance. Imagine Max makes a contract to sell Beth a rare South American monkey and deliver the monkey in six months. If three months into the contract, their state passes a law prohibiting the sale of the monkey because it was granted endangered species status, the contract will have become void, because what was once a legal purpose had become illegal due to a change in law.

VOIDABLE CONTRACTS

Don’t confuse void contracts with voidable contracts. Voidable contracts are otherwise valid contracts that can be avoided, usually by the choice of one of the parties. You may recall we talked about voidable contracts last lesson, when we said that parties must have legal capacity to enter a contract. Minors, mentally ill persons, and intoxicated people can enter into contracts with others, but the contracts are voidable. If the minor, mentally ill person or intoxicated person chooses to avoid the contract, the court may decide the contract is void and unenforceable. Remember, the choice to avoid the contract lies with the person who lacks legal capacity. If the person lacking capacity decides to go ahead with the contract, the contract remains enforceable against the other party.

Other circumstances than can create voidable contracts are agreements made under duress, undue influence, fraud, or physical threat. In each of these circumstances, we feel that the unfair treatment of one party provides the wronged party with the opportunity to avoid the contract.

Finally, one other voidable contract is the unconscionable contract—a contract that no reasonable person would agree to and no honest person would expect to make. Imagine, for example, an art expert is browsing the stalls at a flea market and comes across an original painting by Van Gogh, offered for sale by someone who is completely unaware of art or Van Gogh. The art expert asks the seller how much he wants, and the seller off-handedly shrugs and says, “50 cents.” The art dealer exclaims, “It’s a deal!” He snaps up the painting, tosses a dollar to the seller, and leaves the flea market. The painting is subsequently valued at $20 million dollars. The agreement between the art expert and the seller is arguably void because it is unconscionable. The art expert, who knew the value of the painting, received a massive windfall due solely to the seller’s ignorance of what he was selling. If the seller wished to sue, he would stand a fair chance of recovering the painting because the contract was unconscionable.

UNENFORCEABLE CONTRACTS

An unenforceable contract is any agreement or contract that is unenforceable. We’ve mentioned quite a few unenforceable contracts in this lesson already. Many of them, like the voidable contracts, are valid contracts that one of the parties makes unenforceable by exercising an option. Others, like the illegal drug supply case, may include all the essential elements of a contract, but are unenforceable by operation of law. Another example of an otherwise valid contract rendered unenforceable by law would be an oral agreement for the sale of real estate. The parties may have agreed on every detail—price, conditions, closing date—and yet still the contract would be unenforceable because it was not written, and therefore violated the statute of frauds.

In all of these instances, when a court deems a contract void or unenforceable, the parties’ legal obligation to perform ends and the parties lose access to the courts for contract enforcement. Such contracts have no further legal effect.

Key Terms

Executed Contract

A contract in which both parties have completely performed their contractual obligations.

Executory Contract

A contract in which one or both parties have not yet completed performance of their obligations.

Valid

Having force, or binding force; legally sufficient and authorized by law.

Void

To have no force or effect; that which is unenforceable.

Voidable

That which is capable of being adjudged void, but is not void unless action is taken to make it so.

28.3.a Legal Effects of Contracts Infographic

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the Infographic below.

28.4 Performance

Transcript

INTRODUCTION TO PERFORMANCE

What do you get when you mix together offer and acceptance, consideration, two parties with the legal capacity to make a contract, and a legal purpose? You get a legally enforceable contract that binds the parties. So what happens next?

Next, the parties have to keep their promises to one another. They need to do what they said they would do and perform their respective obligations under the contract.

What exactly do the parties need to do? They need to do whatever the contract says and only what the contract says. Neither party has to do any more than they agreed to do, and once they've done it, their obligation under the contract ends. No one, not even a court can force them to do more. When both parties have fully performed, the contract is complete. It becomes an executed contract, and it terminates.

Full performance by both parties is the best way to terminate a contract. If both parties fully perform, then each party gains the benefit of the bargain they made, and the parties don’t need a court to enforce the contract. Most contracts terminate just this way—with both parties fully performing and happily going their respective ways.

There are, however, less pleasant ways to terminate a contract. A court has authority to terminate a contract if the contract is void or voidable, as we discussed in a previous lesson.

A court also has authority to terminate a contract when a party commits a breach. A breach occurs when one party—or both parties—fails to perform as the contract requires. If one party breaches, the other party may sue, which is how the court gets involved. Once the contract dispute is before the court, the court can decide whether any of the parties has breached the contract and award damages to compensate the non-breaching party. Or the court can order the breaching party to specifically perform as the contract requires. If the court terminates the contract and issues a damages award, the contract terminates, and the parties are no longer bound to perform. Instead, they have to comply with the court’s order. Obviously, this is the least preferred method for terminating a contract.

MOST CONTRACTS PROVIDE THAT ‘TIME IS OF THE ESSENCE’

Most contracts include a “time is of the essence” clause. A “time is of the essence” clause requires the parties to perform their obligations by a specified time. If the parties haven’t performed by the date set in the clause, they are in breach of contract.

A time is of the essence clause is an important lever in a real estate sales contract because without the clause, time—well—isn’t of the essence. Consider the following story. Charlie agrees to buy Lucy’s house and the contract says closing will occur “on or about September 12.” The closing date nears and Charlie calls Lucy and says he’s not quite ready. There’s a problem with the loan and he needs a few more days. Lucy says, “OK.” They schedule a new closing for September 19. Just before the new closing, Charlie calls again and tells Lucy he needs just a few days more. What can Lucy do? If the contract does not contain a “time is of the essence” clause, Lucy may not be able to do much except wait patiently. Although the contract set a date for the closing, the contract did not say the date was important. Courts have a habit of trying to preserve contracts whenever possible. If Charlie is trying to perform, but he needs more time, a court is likely to say the delay is not a breach unless the delay becomes excessive.

A “time is of the essence” clause can firm up Lucy’s closing date. It will make Charlie’s failure to perform by the closing date a clear breach, giving Lucy the opportunity to ask a court for help if she feels she needs it. However, a time is of the essence clause is a double-edged sword, because the clause requires both parties to perform by the specified date. If Charlie doesn’t have financing and Lucy hasn’t cleared title to her property by the closing date, both parties may be liable for breach, because neither was able to perform on time.

REASONABLE TIME

If a contract does not specify a fixed time for performance, courts usually say the parties have to perform within a “reasonable time.” This rule is a natural offshoot of the duty to perform in good faith that we discussed a few lessons ago. What is a “reasonable time” depends on the nature of the contract and the circumstances of the specific case. A truck driver transporting perishable fruit must perform more quickly than a contractor building a skyscraper.

For example if you notice that a contract does not provide any completion date. If possible, suggest the drafter include a date before the parties sign the contract. Leaving the performance date open invites unhappiness and disagreement, because the parties may have two very different ideas about what constitutes a reasonable performance time. Moreover, some courts may even consider a contract invalid if it doesn’t specify a time for performance because courts generally consider timing an essential material term of a contract. This is natural. When you make an agreement, don’t you want to know when the other party will finish? It is the mark of a true professional to pay attention to this fact. Your clients will be happy if you point this out and make sure you have their best interest at heart.

It’s best to keep timing issues in mind while performing and drafting contracts. If a contract includes a “time is of the essence” contract, try to keep performance on schedule. If it looks like you might miss the deadline, contact the other party and try to negotiate a new performance date before the deadline hits. If the contract doesn’t have a “time is of the essence” clause, you should still shoot for the stated performance date. Timing is always important, even if it’s not “of the essence.”

Key Terms

Time is of the Essence

A condition of a contract expressing the essential nature of performance of the contract by a party in a specified period of time.

28.5 Assignment and Novation

Transcript

INTRODUCTION TO ASSIGNMENT AND NOVATION

So far, we’ve talked about how two people create a valid contract. Usually, these two people owe one another a duty to perform under the contract. If either party fails to perform their obligations under the contract, they commit a breach. The other party could sue the failing party in court to enforce the contract through specific performance or to collect money damages.

But what if one party can’t perform? Or just doesn’t want to perform? Is breach the only path forward?

No. Through the magic of assignment and novation, a person can have someone else perform the contract in their place. Although assignment and novation are similar, they differ in important ways. By the end of this lesson, you will understand the difference between the two and have a sense of how people use these mechanisms in real estate.

ASSIGNMENT

An assignment occurs when you transfer your rights and benefits under a contract to someone else. We call the person who gives the assignment the assignor. We call the person who receives the rights and benefits under the contract the assignee.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine Sue and Ted have a sales contract. Sue agrees to pay Ted $250,000 in cash for Ted’s house. The closing nears, and Sue finds another house she likes more than Ted’s. She tells her friend Willa she wished she hadn’t agreed to buy Ted’s house because she loves the new house. Willa excitedly says she’d love to buy Ted’s house. Sue assigns her rights under the sales contract to Willa. Willa shows up at closing with the assignment contract and $250,000 of her own money. What happens?

Well, unless a law or a contract provision prohibits the assignment, Ted must accept Willa’s $250,000 and give her a deed. Willa, as Sue’s assignee, steps into Sue’s shoes. By paying the $250,000, she gets to exercise Sue’s right to receive Ted’s house in exchange. Because Ted gets the expected benefits of the contract—$250,000 in exchange for his house—Ted cannot complain.

Notice, however, that I said Ted must accept this assignment “unless a law or contract provision prohibits the assignment.” Contract language governs the assignment right. If the contract says nothing about assignments, assignment is usually permissible. However, if the contract does address assignment, then the contract governs whether—and how—a party can assign their rights under the contract.

There are other limitations on assignments. Courts usually won’t allow assignment of contracts that involve personal services, like an architect’s services or a real estate agent’s services. Because contracts for personal services involve unique individual skills, courts assume these skills are a material inducement for making the contract and they are reluctant to alter the deal. Courts also won’t allow an assignment if the assignment would violate public policy. For example, many states don’t allow employees to assign future wages.

However, contract language is the primary controller of assignments. Most contracts specify whether they allow or prohibit assignment. Leases often prohibit assignment. Property owners usually want to make sure their tenants can and will take care of the leased property and pay their rent for the full term, so owners usually forbid assignments to make sure the original tenant remains the tenant throughout the lease. However, sales contracts may not address assignment. Sometimes, parties negotiate how the contract will handle assignments because one party is counting on assignment.

For example, during a hot housing market, real estate speculators often used assignment contracts to profit from rapidly rising prices. As an example, let’s go back to Sue, Willa, and Ted. Imagine that instead of finding a new house to buy, Sue just knew that Willa was willing to pay $270,000 for Ted’s house. Sue contracts with Ted to buy his house for $250,000 and then assigns her rights under the contract to Willa in exchange for $20,000. At closing, Willa gives $20,000 to Sue for the assignment and gives Ted $250,000 for the house. Ted must follow through on the deal because their contract did not prohibit assignment. By assigning her rights to a more highly motivated buyer, Sue earned $20,000.

Another common example of assignments in real estate is when lenders assign the income streams from mortgage loans to third parties. The practice is so common that closing documents mention the issue expressly, and buyers often receive assignment notices shortly after closing—if not at the closing itself. The assigned income streams under the promissory notes are often bundled together in investment vehicles called mortgage-backed securities.

I should note one more aspect of assignments. Although you may have assigned the benefits of a contract to someone else and expect them to perform your obligations, your contracting partner may still be able to hold you liable if your assignee fails to perform. If Sue had come to the closing and Willa wasn’t there, Sue still would have had to buy the house. Ted is entitled to have someone perform Sue’s obligations, and if Willa doesn’t do it, then Sue must.

NOVATION

Now, if you really want to end your obligations to the other party in a contract, the mechanism you want is novation. Novation is the process of substituting a new obligation or contract for an old one. Unlike assignment, however, novation requires both parties to agree to it. Novation usually results in a completely new contract, under the same terms, but with different parties. Unlike assignment, novation usually releases one of the original parties from their obligations.

A prime example of novation in real estate is the assumption of an existing mortgage by a new buyer. When the lender agrees to it, the parties execute a novation at closing that substitutes the new buyer for the old debtor and imposes all the existing obligations of the original mortgage loan on the new debtor. The novation creates a new contract between the lender and the buyer, and, unlike assignment, the seller leaves the transaction free of obligation.

Key Terms

Assignment

A transfer to another of any property in possession or in action, or of any estate or right therein. A transfer by a person of that person’s rights under a contract.

Novation

The substitution or exchange of a new obligation or contract for an old one by the mutual agreement of the parties.

28.5a Assignment and Novation Infographic

Please spend a few minutes reviewing the Infographic below.

28.6 Discharge of Contracts

Transcript

INTRODUCTION TO DISCHARGE OF CONTRACTS

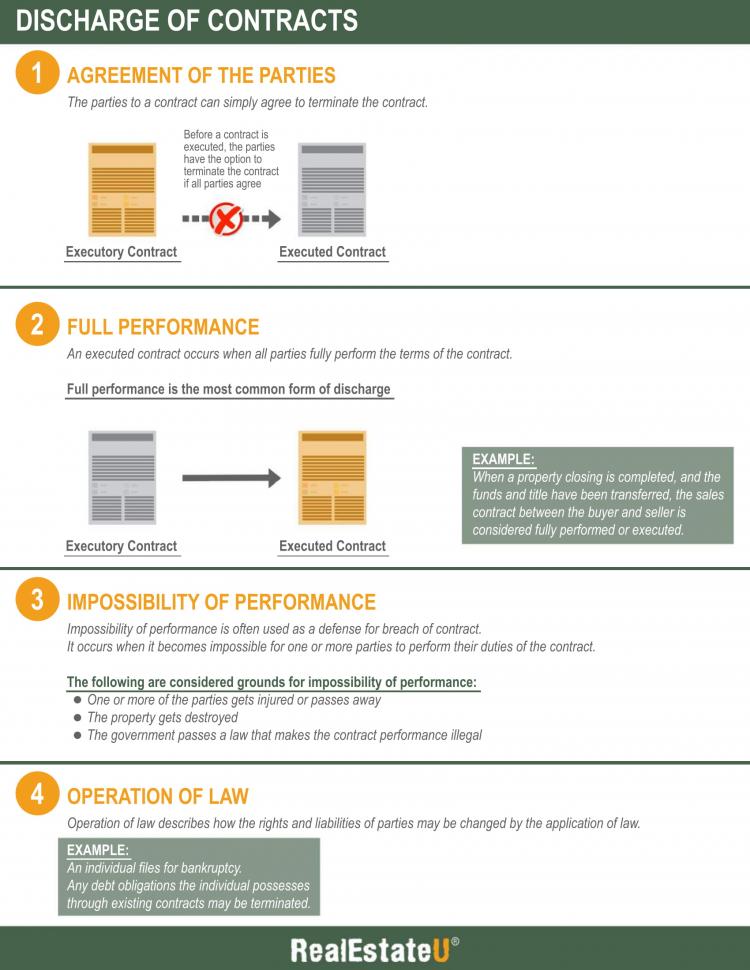

Two lessons ago, we talked about how to terminate a contract. Then, I mentioned that the best way to terminate a contract is for both parties to perform fully. In this lesson, we dive more deeply into the many ways a contract can end—or, as the lawyers like to say—how a contract is discharged.

We can discharge a contract in five major ways. A contract can end in some other, less common, ways, but the five we are going to talk about are the major methods for discharging contracts.

The first way is when the parties mutually agree to end the contract. The second is when the parties fully perform their respective obligations under the contract. The third way occurs when unexpected events make a contract impossible to perform. The fourth way is when an operation of law renders the contract unenforceable. The fifth way is when a party breaches the contract, and a court order discharges the contract, with or without a damages award.

We’re going to talk about each kind of discharge in turn in this lesson. But before we do that, let me tell you a story.

Ernesto owns a movie theater downtown called the Vista Theater. The Vista is a lavish art deco theater built in the 1930s. The lobby is full of mirrors and lights and the theater hall boasts four huge crystal chandeliers. In the last few years, ticket sales at the Vista have been falling. Ernesto blames it on binge-watchers staying home to stream television series. Whatever the reason for the falling sales, Ernesto decides to sell. He’s losing money on the upkeep of the theater and he wants out. He lists the Vista at a sale price of $1,000,000.

Maya learns that someone plans to open a new museum just a couple of blocks away from the Vista called the Museum of Movies. Maya believes the Vista’s sales could snap back with the Museum nearby. She believes movie fans attending the Museum during the day would love to catch a movie in the evening at the beautiful Vista. She agrees to buy the Vista from Ernesto. They draw up a contract, with a closing scheduled in six months, to allow Maya time to get financing.

Will the story have a happy ending? Let’s find out.

AGREEMENT OF THE PARTIES

Imagine Maya spends some time looking for financing, but she just can’t find anyone willing to lend her the amount she needs. Imagine that in the meantime Ernesto gets to thinking about the new museum and decides that maybe the future isn’t as bleak as it seems. Maya comes to Ernesto, distraught, and tells him she’s having trouble finding financing. Ernesto says, “Hey, why don’t we call the whole thing off?” Can they do that?

Yes! Those who agree to be bound can also agree to be unbound. To do this, the parties must make a new contract—a binding and enforceable agreement that the original contract will no longer be enforceable.

The new contract, however, will require mutual agreement and consideration, just like any other contract. What is the consideration for agreeing not to enforce the original contract? The answer depends on how much the parties have already performed.

If neither party has begun to perform, then consideration for a discharge by agreement is simple. Each party’s waiver of the other’s performance obligation is the consideration for the agreement.

Let’s go back to Ernesto and Maya for a moment to make this point clear. Under the contract, Ernesto and Maya each hold a legal right. Ernesto can require Maya to pay $1,000,000 to buy his theater, and Maya can require Ernesto to convey the theater to her for $1,000,000. By giving up their respective legal rights to require the other to perform, Ernesto and Maya will each experience a legal detriment, and legal detriment, you may recall, is consideration for a contract. Voila! Mutual agreement and consideration.

Discharge by agreement before performance is the simple case. But what if one of the parties has already started to perform? This situation is trickier because just calling off the contract after performance has begun would unjustly enrich or detriment one of the parties. For example, imagine that instead of selling a theater to Maya, Ernesto is building a theater for her. If Ernesto completed half the building, and Ernesto and Maya wanted to call the agreement off, Maya would receive half a building, and Ernesto would receive nothing. In this case, both Ernesto and the courts would expect Maya to pay Ernesto something before discharging the contract. That “something” Maya pays would be the new consideration for Ernesto not suing on the original contract and asking the court to order her to pay damages.

When the parties agree to discharge a contract, the legal result is that the original contract becomes unenforceable. If a party sued on the old contract, the defending party would point to the new discharge contract. In many ways, you can think of this whole process as novation—the replacement of an existing contract with a new contract, where you are changing obligations instead of changing parties.

FULL PERFORMANCE

By far, people’s favorite form of contract discharge is full performance by both parties. Everybody gets what he or she expects out of the contract. Everything is resolved. Life is good. The parties go their separate ways, mutually enriched and free of obligations.

So who declares the contract discharged? A formal announcement may not happen. In the case of an executory contract (a contract yet to be performed), the contract is alive because parties are expecting performance to occur. If a party breaches the contract by failing to perform, the non-breaching party can file suit in court to enforce the contract. Both parties know this. This pressure of expectations keeps the contract obligations in the parties’ minds.

But once full performance occurs and the parties’ expectations are met, the executed contract is “dead” in the sense that nobody is expecting anything further to happen. If a party sued on the contract, the court would dismiss the case because the parties had completed all their obligations. The contract no longer governs the parties’ behaviors. Even without a formal discharge, the contract is discharged by virtue of having served its purpose. The parties move on.